1991.10.04 - L.A. Weekly - Guns N' Roses: Up From Nowhere

2 posters

Page 1 of 1

1991.10.04 - L.A. Weekly - Guns N' Roses: Up From Nowhere

1991.10.04 - L.A. Weekly - Guns N' Roses: Up From Nowhere

Transcript:

----------------------

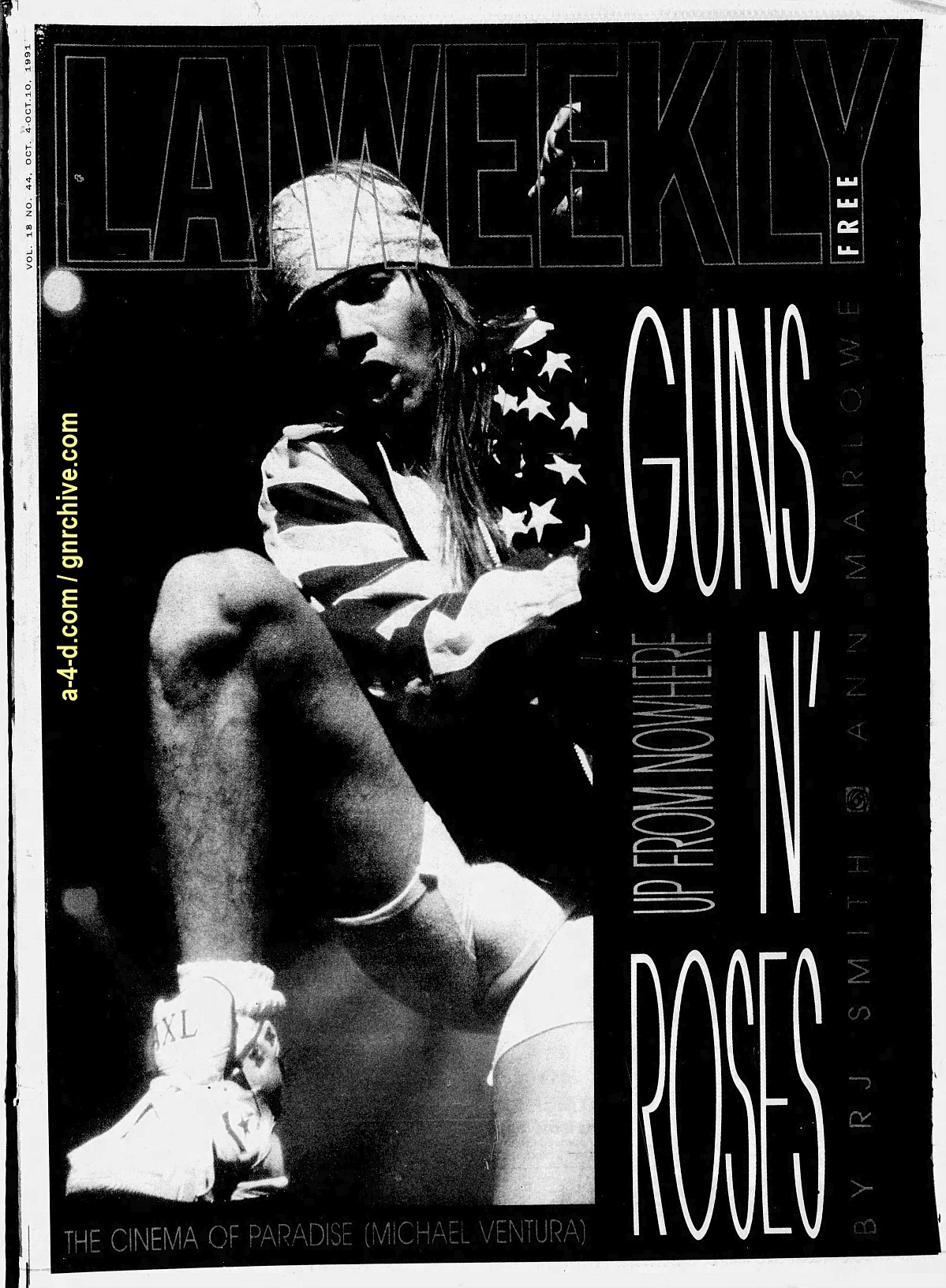

GUNS N' ROSES

UP FROM NOWHERE

***

GUNS N’ ROSES

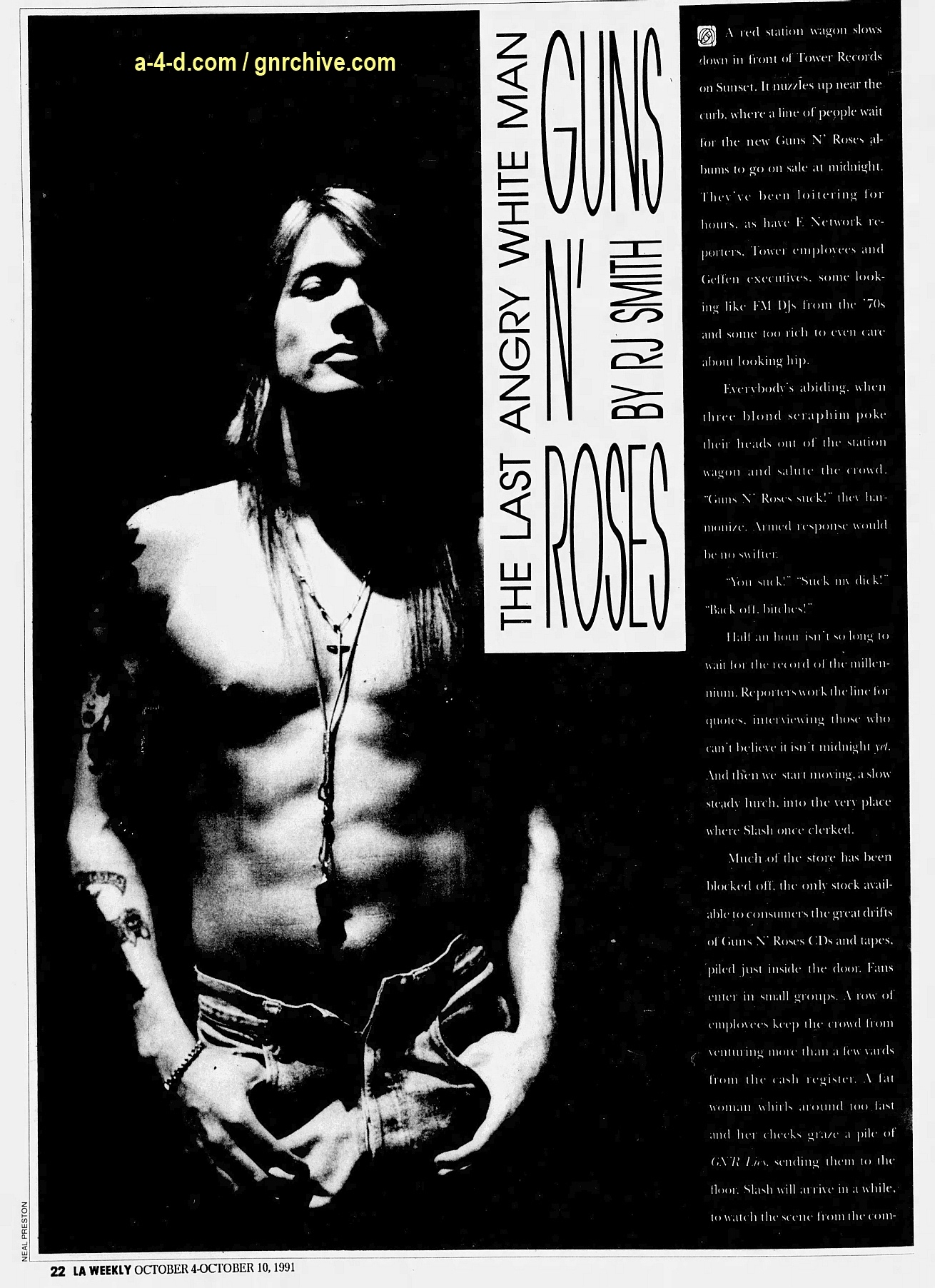

THE LAST ANGRY WHITE MAN

BY RJ SMITH

A red station wagon slows down in front of Tower Records on Sunset. It nuzzles up near the curb, where a line of people wait for the new Guns N’ Roses albums to go on sale at midnight. They’ve been loitering for hours, as have E. Network reporters. Tower employees and Geffen executives, some looking like FM DJs from the ‘70s and some too rich to even care about looking hip.

Everybody’s abiding, when three blond seraphim poke their heads out of the station wagon and salute the crowd. “Guns N’ Roses suck!” they harmonize. Armed response would be no swifter.

“You suck!” “Suck my dick!” “Back off, bitches!”

Half an hour isn’t so long to wait for the record of the millennium. Reporters work the line for quotes, interviewing those who can’t believe it isn’t midnight yet. And then we start moving, a slow steady lurch, into the very place where Slash once clerked.

Much of the store has been blocked off, the only stock available to consumers the great drift of Guns N’ Roses CDs and tapes, piled just inside the door. Fans enter in small groups. A row of employees keep the crowd from venturing more than a few yards from the cash register. A fat woman whirls around too fast and her cheeks graze a pile of GN’R Lies, sending them to the floor. Slash will arrive in a while, to watch the scene from the comfort of his limousine before he leaves to dine at Le Dome. I get the nod from a beefy doorman, walk up to a skinny clerk in a Mary’s Danish T-shirt, and ask him something that’s been eating me all evening.

“Do you have the new Richard Marx album?”

He fidgets, cranes his head to the right, left, right.

“Well, we do have it. But you can’t buy it tonight.”

*

THESE ARE GN’R TIMES. IT WAS ALL well and good when Metallica went to the top of the charts, and nice of Garth Brooks to warm up the seat last week. But now, Use Your Illusion I and II stare out like evil eyes from on high. Get used to it.

Few records have been so outsized. There are 30 songs on both Illusions, and they clock at more than 20 minutes longer than Exile on Main Street and London Calling combined. Except, heh heh, the Illusions are no normal double album. You have to buy them separately, without the discount that usually accompanies two-fers.

As for the band, they have inflated their tough-guy image, which now towers like a prairie jackelope. We are out of control, man, and if you don’t believe it you can just get in the ring, motherfucker! They’re big and bad enough to have unprecedented control over what is said and written about them. Their 1987 Appetite for Destruction sold more than any debut in history — 13 million. The first leg of their current tour completed, they are more awesome media objects than Madonna, though less fabulous ones. And this tour, the first they’ve headlined, is going to last two years. Of course they had to sell their record at midnight in stores across America: how else were children to get any sleep that night?

Not all of their followers are Strip denizens or 7-Eleven outdoor furniture. But it is the working-class fan, and those at the bottom rungs of the middle class, who stick up for Guns N' Roses. Nobody sensationalizes the band more than GN'R do themselves, but their success is based on their ties to an audience so undervalued and unglamorous that they often seem not to exist. Appetite for Destruction made a life of waiting around and cooking up schemes seem exciting: if the band half-chose their idleness, it was taken to heart by a nation of teenagers who had downtime forced upon them.

In 1988, singer Axl Rose and the band recorded “One in a Million." Included on GN'R Lies and never released as a single, if it is not their most famous song, it is the one that cuts deepest. “One in a Million”’s lyrics are well-known and reviled: "police and niggers, that’s right/get out of my way/don’t need to buy none of your/gold chains today” and “immigrants and faggots/they make no sense to me/they come to our country and think they’ll do as they please/like start some mini- Iran/or spread some fucking disease.” The song brought on a torrent of criticism. Yet if Rose’s (and Geffen’s) denials of racist/homophobic content seemed preposterous, they weren’t the only ones evading an issue. Critics — most of them college-educated, from the middle class — were also running away from something. There was, I think, some hate for GN’R’s audience mixed in with the hate critics expressed for Axl’s words. The song penetrated not only because of the words but because of the performance. Eerie and restrained, Rose sang open-heartedly, like Rod Stewart confessing to Maggie May, and like a folk singer who knows he has something prophetic to share. “One in a Million” made you feel what the singer felt: a fear that melded all enemies, and maybe everything in the whole world, and a wish to annihilate. Then, after the hate, it begged your forgiveness, polite as any boy from Indiana new to the city. I don’t think many critics simply hate Rose for saying certain words. They hate him for making them feel things they lock up in themselves.

Rose has since apologized in his fashion; he saves his fits for “bitches” and magazine editors these days; and GN’R aren’t performing “One in a Million” anymore. All the same, I wonder if Rose hasn’t done all right by “One in a Million.” It has served his popularity in the way “quotas” or “Willie Horton” have served other folks. “One in a Million” signaled, in a subterranean way, his blood ties to the white working and lower middle class. Fans knew he came from the heartland; the people who paid far and away the highest price in the wake of the advances of the civil-rights agenda knew it best of all. “One in a Million” set Rose's image as another great American populist, singing a song and telling the children to stand up, like Woody Guthrie or Charles Manson.

*

AXL ROSE FLATTERED LOS ANGELES from the moment he stepped off the bus at the downtown station. I’ll play the game your way, he’s always admitted (and intoned: I’ll make you suffer for it). He’s the greatest small-town-doe-made-good since James Dean.

But while he catered to the legend, Rose played it out to a bigger crowd than the one in the Cathouse. In L.A. his savvy made him look like an exemplary nobody with a hard- on for fame; at large, he looked like an idler who wasn’t letting it get him down. At a time when the country was relaying a message to metal’s working-class constituency that they could not count on anyone else, what gave life meaning was a hustle successfully converted. “The deal” has always been a permanent part of the Hollywood myth, but in the Reagan years it was the country’s new foundation. Whole families were living off the books, and the attitude was everywhere — no wonder Donald Trump is a GN’R fan. Appetite for Destruction was about reading the codes of the hustle, and making them work to your advantage. In interviews Axl said young musicians should take business courses so they would not get fucked over; in “Welcome to the Jungle,” he said “If you want it you’re gonna bleed/but it’s the price you pay.”

Guns N’ Roses did not return glory to teenagers who’d been denied it for perhaps their whole lives, as did Bon Jovi in one way and Metallica in another. They didn’t fantasize about swords and sorcerers or de debbil. They were realists. Cynical about the way things worked (“Captain America’s been torn apart/Now he’s a court jester with a broken heart”), they held on to their sense of humor. The loose story on Appetite was about a band and the company they kept while trying to make it big. Beneath that was the idea that right here, right now, hope could cost you. They paid to play, and then they made you pay.

Money changes hands all over Appetite, prostitutes and groupies picking up change off the street. Relationships are defined by economic fact; the frenzy of making do is the subject and the high that powers the album. Like hardcore rappers, GN’R were interested in making money. Unlike rappers, GN’R allowed themselves to feel conflicted.

Their debut is a hustler’s handbook, but it also announces that what they really want, they might never get. “Paradise City” and “Sweet Child o’ Mine” describe states of bliss that the singer would seem to know are unattainable. These are songs of regression, hurtling back to a place where nobody can hurt you. They are utopian and infantile, and when you see Rose sway his hips on stage, he takes you with him. The two songs that express the most oceanic feelings in this generation are anchored in the past. “Turn me around and take me back to the start,” Rose says in “Paradise City” — because that was the last, best hope. The songs connect deeply with a nation of fans who saw the safety net roll up on graduation day, who were told by a president who read the want ads that it was their fault if they didn't have a job. Dad had it better, and your kids would have it worse.

Something Ice Cube has said more than once about utopian black nationalism: “It’s a beautiful dream. But it’ll never happen.” “Paradise City” and “Sweet Child o’ Mine” are Axl's utopias, and he can’t slough them off so easily. His dreams cut him in half. Listen to him sing.

*

THERE ARE MORE BALLADS BUT LESS bliss on Use Your Illusion I and II. They are the angriest two records to ever sit at the top of the charts. These are, people in the strangest places keep saying, hostile times: “Americans are angry, not apathetic,” writes Jerry Brown in a letter to supporters, “de-facto disenfranchisement has been answered by deliberate disengagement.” If the Illusions keep selling gazillions once the curiosity built from four years of waiting is over, it will be because Axl’s rage hooks up with millions of Americans looking for a way past their apathy and finding only anger.

The inner child has got a gun, and baby’s learning how to use it. Connoisseurs should leap right to “Shotgun Blues,” a murder fantasy allegedly aimed at Motley Crue’s Vince Neil. Its speed makes the hairs on your neck stand on end. But if “Shotgun” is one of the shortest songs on these records (a slender 3:23), even here Axl finds time to let himself off the hook: “I said I don’t know what I did/but I know I gotta move” he sings out of a hole in the top of his skull. Then some poor guy’s worst thoughts are splashed against a wall.

Given the volume of music here, songs do tend to blur one into the next. What stays level is Rose’s dissociation. He doesn’t want credit or culpability, he says again and again, perhaps nowhere more clearly than in this line from “Don’t Damn Me”: “I never wanted this to happen / Didn’t want to be a man.” Don’t blame me— not for what I say, for the mess I make of my life, for what I’m about to do to your face, for the next 30 things that get reported in Spin.

I really like “Shotgun Blues,” but you hear this sort of thing for a couple of hours and Axl starts sounding like some child actor left alone in a store and asked to pay for what he wants for the first time in his life. He looks around, like they just don't get it. And then he starts bawling.

According to a story going around, Rose thinks aliens are living in his abdomen, where they tape-record his thoughts. Should they ever release these sessions, let us hope the invaders get a producer unafraid to tell them no. There is the core of a great single album in Illusion: “Dust N’ Bones," “Bad Apples,” “Coma,” “Civil War,” “Shotgun Blues,” “Pretty Tied Up,” a few others. But if Use Your Illusion is an epic, as is predictably enough being written, don’t think Exile on Main Street: think Our Hitler.

There are problems other than length. Guns N’ Roses had in Steven Adler a stiff-backed punk-rock drummer who knew his way around disco beats. When they let him go (too many drugs, the band says: not enough drugs, Adler says) before recording Illusion, he was replaced with Matt Sorum, one of the steadiest hands you’ll never want to hear. Sorum’s the most practical musician in the band, and the kind of lean tactician who idolizes Al Jackson or Max Weinberg for their precision.

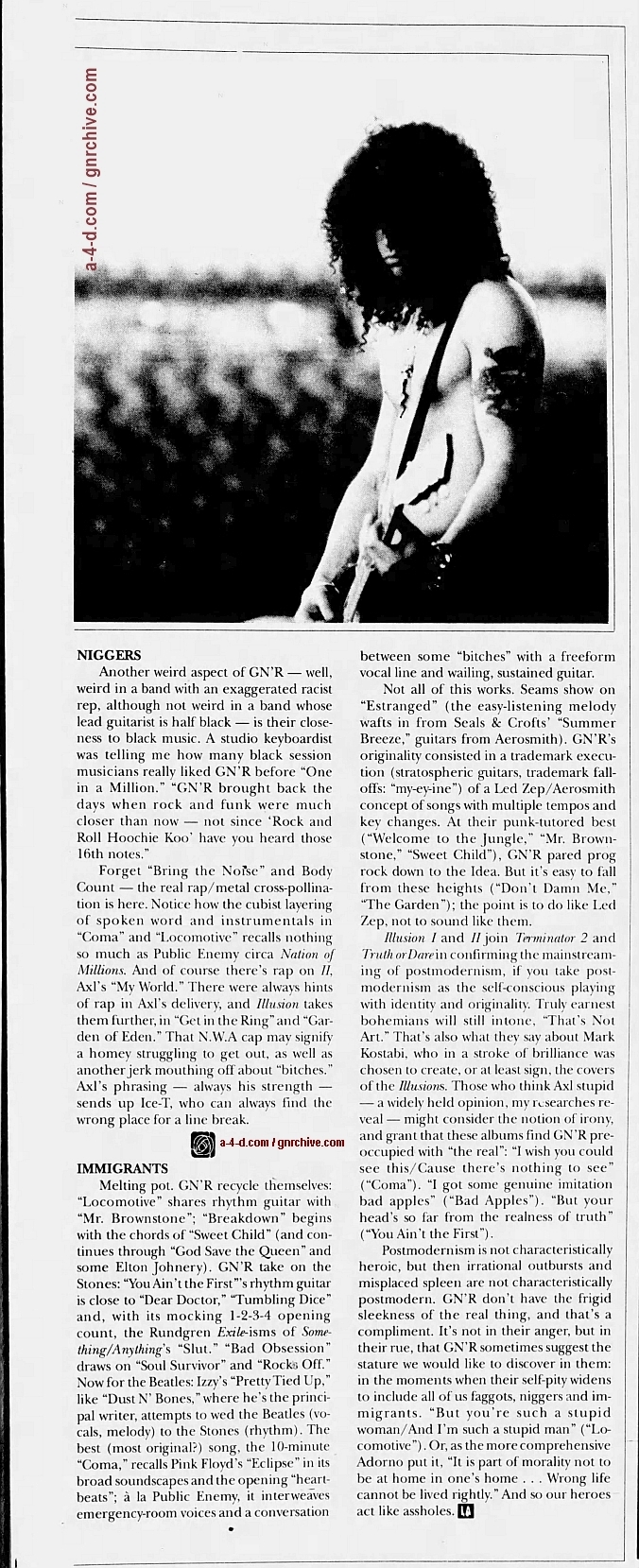

Guitarist Slash revives the once commonplace knack for melding rhythm and lead playing. But he remains a spokesman for knowing your limits. If his solos fish around for melodies they never quite settle on, they do not seem lost; once he steps off a riff he starts flailing and yet he holds your attention. If the Stones-Aerosmith continuum GN’R tapped so deeply on Appetite still serves them here, it’s been buttressed with Beatles and Pink Floyd touches, and the spirit — though not the sound — of Ennio Morricone’s film scores. While the arrangements sometimes get florid, Slash and guitarist Izzy Stradlin aren’t affected, and their playing lifts up even a woozy psychedelic tune like “The Garden.”

The guitars are one anchor for Use Your Illusion I and II. Another is the proliferation of perverse, indulgent non sequiturs, like Axl reciting a Cleavon Little monologue from Vanishing Point at the end of “Breakdown,” or the way he almost undoes the majesty of “Civil War” for the sake of a stupid line at the end: “What’s so civil about war anyway?” And what’s the deal with that murky, guttural voice that surfaces throughout the album, like the voice of Axl’s evil twin (actually, it kind of sounds like Artie Johnson’s dirty old man)?

The weirdest thing on the record is also the finest song, the 10-minute-long “Coma.” It’s a sick slide into catatonia, perhaps drug-induced. All over this record, Rose sounds like a paranoid schizophrenic, veering from delusions of grandeur to fears that everybody is out to get him. On “Coma,” those poles are given a voice, and try to kill each other. Hardcore punk rooted out all foreign influences, inhumanly saying over and over again that you can’t trust people who aren't exactly like you; hardcore fan Rose takes this even further, carrying the retreat from the world into his own cranial dome, where he curls up and refuses to leave. He says he wants to die because that’s the only peace possible, and then he has his doubts...

Last week, eight scientists climbed into Biosphere II, a 3.15-acre glass multiplex in Arizona’s Sonoran Desert. They will live there for the next two years, foregoing physical contact with the outside world. Think of this dome as Axl Rose’s head. But where does the garbage go?, little children ask. They will raise plants and animals and recycle everything in this totally isolated environment. The medieval reliance on the state or society or the military-industrial complex will be annulled. What happens to all the shit?

An at first unpromising metal riff which has been rising and falling throughout the song descends again, and suddenly it feels essential. Sorum kicks a hole in his drum, there is a whistling sound, and the structure explodes — glass, shit and clotted spores representing the earliest stages of human existence all roll out over the desert floor. The song seems to be saying the past is over, time to deal with life here and now. “Coma’”s the brilliant end of something. Unfortunately, it’s only the middle of the Illusions.

*

ANOTHER SET OF LINES, THESE from “Right Next Door to Hell”: “My mama never really said much to me/she was much too young and scared ta be/hell ‘Freud’ might say that’s what I need/but all I really ever get is greed.” Miles from paradise, in an edge city where greed is all... That is where the Illusions play out.

But where Rose once held onto his cynicism as he climbed the ladder, now he’s a one-in-a-millionaire, and if greed is all around, its list price is $11.99 per Illusion. Rose can’t simply damn the greed; he can’t roast his work ethic. And he doesn’t have the cynicism to come up with a song that might crystallize his condition, the way the Stones did in “Salt of the Earth." The Stones made a little bonfire of their good intentions, and came up with a sad, beautiful song about the distance between them and the working class.

There’s more violence, hate and nausea across these records than there was on Appetite. What makes Axl’s spite dance like spit on a griddle is his paralysis: these are songs made by somebody who pays millions for a new house, and then pushes a grand piano through the wall the first night he moves in. Conflicted about our wealth, are we? Here’s Axl talking to a Musician interviewer: “I find more and more that I have less in common with my fans... Or that I have certain things in common with my fans, but they don’t have things in common with me.”

That sounds like a pretty conservative definition of an artist: somebody who knows his audience, but who thinks his audience will never understand him. Anybody who’s seen Rose throw his head back and flail his arms at the piano while he essays “November Rain” knows he’s on a mission to share his feelings. It’s what we ask stars to do. Maybe most of all, it’s what happens to those who come out of a working-class background: speak to the voiceless and you may find yourself speaking for them. Rap has increasingly turned into a music made by spokesmen ready with a moral prescription. Axl Rose holds on to his ambivalence about his new status as role model, but he’s ready to bare his soul.

He’s been elected. Rose looks for something to express, digs for a mood to share, and all he can find is a main vein of hate. Some of the ballads are nice, and “Civil War” has an anti-war text that takes us beyond Rose’s head, but these are exceptions. Inside fortress Axl the deepest feelings you find are the ones that go bitch, bitch, bitch, I wish your ass was dead.

There are verdant riffs, evocative guitar solos all over Use Your Illusion I and II, but what you remember is the heat. The blinding rage. The more he earns, the less he knows what he really wants. Next album, Rose may turn into Darby Crash. These records belong to the genre of songs about the perils of stardom. Maybe Axl is a person who should never have been a star: he got what he wanted and it makes him howl. And if life in the marketplace fucks him up this bad, what does it do to people who can’t afford to wrap a new car around a fresh telephone pole every day of the year for the rest of their life?

***

THE NEW AMERICAN HERO

BY ANN MARLOWE

The hero, after all, is not a model for imitation, but rather a figure who cannot be ignored.

—James Redfield, describing Achilles, in the introduction to Gregory Nagy’s The Best of the Achaeans

*

PEOPLE GET MAD WHEN I CALL AXL Rose a hero. What’s he done, they ask, besides toss epithets and tantrums in public? Think of the influence he could have — let’s see, donating 10 percent of the band’s take on the 1.5 million albums sold Thursday would save how many acres of rain forest? Read the Redfield quote again. Axl is a hero, like Achilles, and a childish asshole, also like Achilles, and a hero anyway. Names are pretty similar, too, and Axl even went around with a hurt foot this summer. And we care enough about GN’R to wait in line at Tower Records or to hate not just their music, but everything they stand for.

Who else moves us this way? Maybe N.W.A, more likely Madonna, who also evokes unreasoning hatred and love. But where Madonna purveys different images of herself with exquisite, self-mocking control, Guns N’ Roses are prisoners of their market-ready rage and static rocklook. Madonna markets stardom; Axl portrays the star as persecuted naif. Next to the triumphant icon Madonna presents, GN’R look like victims. And that’s the way they want it. If you forgot the whip when you went to visit them, what would they have to say?

Along with N.W.A, GN’R have made a career of marketing ressentiment. Their characteristic utterance — like Achilles’ — is the complaint. But where N.W.A are happy to make themselves loathsome, GN’R want to be loved. Paradoxically, this is behind the whining and Axl’s endless kvetches. All demands are demands for love, Lacan wrote: all demands. This makes Axl's appeal understandable: he’s a man who wants too much to be loved. In songs like “Get in the Ring,” with a first verse that’s pure projection (“Why do you look at me when you hate me?” indeed), the oddness of this man’s stardom is more apparent than it ever was on Appetite for Destruction.

GN’R were always strange, but we, and they, didn’t want to see it. Use Your Illusion I and II are long and loose enough to make the oddness inescapable. Far richer, more complex and more confused than Appetite, overweeningly ambitious at 76 minutes each, the two are still unsuccessful as “albums,” in the “concept” sense. But out of the 28 originals, with more care and focus, what an album there might have been. The songs encompass real innovation (“Coma,” “Breakdown,” “Pretty Tied Up,” “Locomotive,” the end of “November Rain”); filler (“14 Years," "Perfect Crime,” “Shotgun Blues,” “Back Off Bitch,” “Double Talkin’ Jive”); interesting messes (“Dead Horse,” “You Could Be Mine,” “So Fine”); rap (“My World”); sloppy slap-rapped speeders (“Garden of Eden,” “Don’t Damn Me”); competent, enjoyable genre pieces (“Right Next Door to Hell,” “Civil War,” “Bad Apples,” “Yesterdays”); exciting idiocy (“Get in the Ring”); and a genuine, if unmotivated, historical first, one mediocre song with two partly different sets of lyrics (“Don’t Cry”).

*

FAGGOTS

The strangeness of the Illusions is explained in part by their hidden goal: to confirm our love. I’d guess that what drives GN’R isn’t crafting the best songs they possibly can; it’s achieving, or at this stage reaffirming, their hold on our affections. Love, Adorno noted, “you will find only where you may show yourself weak without provoking strength.” And vulnerability is crucial to GN’R’s power.

When you come right down to it, who’s less macho than Axl Rose? At this summer’s theater shows, he seemed fresh-faced, small-boned, even fragile; you could imagine his teenage self having reason to fear assault. Drawing on a confusing, or confused, array of symbols, from N.W.A cap to translucent white bike shorts, he seemed more epicene than androgynous, more innocent than decadent, more fragile than dangerous. A boy, and so a particularly appropriate icon for the '90s, when it seems likely that the Man will end his attenuated existence and gracefully disappear. (Wasn’t “You Could Be Mine” on the soundtrack for a movie whose heroes are a boy and his machine?) Because GN’R are boys, teenage girls aren’t threatened by their sexuality. Axl’s sex, even in those bike shorts, is mainly conceptual: “You don’t understand your sex/You ain’t been mindfucked yet” (“My World”).

GN’R’s unsexiness is elusive; the associations they evoke are supposed to carry an erotic charge. But they make signs of being sexy, without being sexy. I don’t find myself fantasizing about fucking them. (Live, only Slash radiates physical appeal — certainly not plump and unctuous addition Matt Sorum, throwing his drumsticks into the crowd as though anyone cared.) GN’R write about pretty mainstream sexual / romantic scenarios, unwilling to flirt with even the mild ambiguities of “Dude Looks Like a Lady” or “Mistress for Christmas.” “Pretty Tied Up”? Best hooks, so to speak, of the bunch, but since when have women in chains and men with whips threatened tradition? And the sex here, as in the other 11 songs that deal with women, never seems much fun. Pleasure is what’s missing, and sadly, we hardly notice.

Caught up in their bad-boy imagery, we forget that GN’R were moralists from the first, spinning tales of Hollywood rocklife more cautionary than celebratory. In the Illusion albums, the band’s lack of exuberance is made conspicuous by their stunning ascent. They’ve won everything, but still they aren’t happy. Americans to the core, they’re becomingly ambivalent about the excess (“I got a headache like a mother/Twice the price of my thrills”) and the success (“Yeah you got to make a living/With what you bring yourself to sell”). And so “Bad Apples” finds Axl peddling us apples, evoking not only the Garden of Eden but the Depression that shadows all American joy.

GN’R’s angst may he necessary for us to enjoy them — not just to deflect our envy, but to allay our guilt. These days, pleasurable music is guilty music. We suspect it, not unjustly, of soullessness; angst seems to show more sensitivity, or at least better taste. Major keys, euphoric guitars and catchy choruses have to be earned, or the listener is complicit in a mindless hedonism that’s supposed to be out of style. Consider rap, or the Lollapalooza bands: their easiness on the ears (compared to the more truly “alternative” thrash, improv and noise bands like the Buttholes of yore) is excused by their clothes, politics or color.

*

NIGGERS

Another weird aspect of GN’R — well, weird in a band with an exaggerated racist rep, although not weird in a band whose lead guitarist is half black — is their closeness to black music. A studio keyboardist was telling me how many black session musicians really liked GN’R before “One in a Million.” “GN’R brought back the days when rock and funk were much closer than now — not since ‘Rock and Roll Hoochie Koo' have you heard those 16th notes.”

Forget “Bring the Noise” and Body Count — the real rap/metal cross-pollination is here. Notice how the cubist layering of spoken word and instrumentals in “Coma” and “Locomotive” recalls nothing so much as Public Enemy circa Nation of Millions. And of course there’s rap on II, Axl’s “My World.” There were always hints of rap in Axl’s delivery, and Illusion takes them further, in “Get in the Ring" and “Garden of Eden.” That N.W.A cap may signify a homey struggling to gel out, as well as another jerk mouthing off about “bitches.” Axl’s phrasing — always his strength — sends up Ice-T, who can always find the wrong place for a line break.

*

IMMIGRANTS

Melting pot. GN’R recycle themselves: “Locomotive” shares rhythm guitar with “Mr. Brownstone”; “Breakdown” begins with the chords of “Sweet Child” (and continues through “God Save the Queen" and some Elton Johnery). GN’R take on the Stones: “You Ain’t the First”’s rhythm guitar is close to “Dear Doctor,” “Tumbling Dice” and, with its mocking 1-2-3-4 opening count, the Rundgren Exile-isms of Something/Anything's “Slut.” “Bad Obsession” draws on “Soul Survivor” and “Rocks Off.” Now for the Beatles: Izzy’s “Pretty Tied Up,” like “Dust N’ Bones,” where he’s the principal writer, attempts to wed the Beatles (vocals, melody) to the Stones (rhythm). The best (most original?) song, the 10-minute “Coma,” recalls Pink Floyd’s “Eclipse” in its broad soundscapes and the opening “heartbeats”; a la Public Enemy, it interweaves emergency-room voices and a conversation between some “bitches” with a freeform vocal line and wailing, sustained guitar.

Not all of this works. Seams show on “Estranged” (the easy-listening melody wafts in from Seals & Crofts’ “Summer Breeze,” guitars from Aerosmith). GN’R’s originality consisted in a trademark execution (stratospheric guitars, trademark fall-offs: “my-ey-ine”) of a Led Zep/Aerosmith concept of songs with multiple tempos and key changes. At their punk-tutored best (“Welcome to the Jungle,” “Mr. Brownstone,” “Sweet Child"), GN’R pared prog rock down to the Idea. But it’s easy to fall from these heights (“Don’t Damn Me,” “The Garden”); the point is to do like Led Zep, not to sound like them.

Illusion I and II join Terminator 2 and Truth or Dare in confirming the mainstreaming of postmodernism, if you take postmodernism as the self-conscious playing with identity and originality. Truly earnest bohemians will still intone, “That’s Not Art.” That’s also what they say about Mark Kostabi, who in a stroke of brilliance was chosen to create, or at least sign, the covers of the Illusions. Those who think Axl stupid — a widely held opinion, my researches reveal — might consider the notion of irony, and grant that these albums find GN’R preoccupied with “the real”: “I wish you could see this/Cause there’s nothing to see” (“Coma"). “I got some genuine imitation bad apples” (“Bad Apples”). “But your bead’s so far from the realness of truth” (“You Ain’t the First”).

Postmodernism is not characteristically heroic, but then irrational outbursts and misplaced spleen are not characteristically postmodern. GN’R don’t have the frigid sleekness of the real thing, and that’s a compliment. It’s not in their anger, but in their rue, that GN’R sometimes suggest the stature we would like to discover in them: in the moments when their self-pity widens to include all of us faggots, niggers and immigrants. “But you’re such a stupid woman/And I’m such a stupid man” (“Locomotive”). Or, as the more comprehensive Adorno put it, “It is part of morality not to be at home in one’s home... Wrong life cannot be lived rightly." And so our heroes act like assholes.

Blackstar- ADMIN

- Posts : 13905

Plectra : 91359

Reputation : 101

Join date : 2018-03-17

Re: 1991.10.04 - L.A. Weekly - Guns N' Roses: Up From Nowhere

Re: 1991.10.04 - L.A. Weekly - Guns N' Roses: Up From Nowhere

I guess this was the review Axl was referring to here:

| [...]Now, I wanna ask your opinions about GN’R. I was reading in a magazine that we should have called these two new records “Our Hitler,” comparing me to Hitler; [that] I’m a troubled child and, basically, I’m Hitler, and if people listen they’ll all go to hell. What do you think of that? Being that we are the band that put out One in a Million, let me ask this question: how many redneck racist assholes do we have here tonight? And do you think that I’m a racist? Or a lot of you are just confused and you don’t know whether I am or not. I live in L.A., I’ve lived there for ten years. I’ve lived on the streets – I don’t anymore, but I used to. And, I mean, we hang out with people like Ice T and NWA. And it’s like, you can use whatever fucking language you want. I don’t need a bunch of jerkoff white fuckin’ people fuckin’ telling you I’m a racist cuz they don’t want our rock ‘n’ roll to exist. I had a meeting about a year-and-a-half ago with Arsenio Hall, cuz he was on TV calling me a racist and shit, and we went out and had a little talk. And he was like, “The reason I’m having this talk is that I suddenly realized that the 70-80% of the white people in my organization were the ones telling me you’re a racist – not the black people that work with me.” It was the white people that didn’t want GN’R to be the fuck around. Okay, if you think that GN’R means, “Do cocaine and party, and basically drive yourself off the fuckin’ cliff, because we just don’t care about life anymore” – is that what GN’R stands for you? GN’R is basically about survival and just getting through it however you can, and learning that you have to deal with what you did do. Just cuz I’m writing a song about how we did junk, it ain’t about telling you to go do fuckin’ junk, you know? It ain’t telling you to do that, but the parents, and the media and shit, want you to believe that. [...] [On stage in Dayton, OH, USA, January 13, 1992] |

| [...] You know, we just put out these records and I’ve read all kinds of reviews. I’ve been called everything. We should have called the record “Our Hitler;” that’s from a review I read. Yeah, I think Guns N’ Roses has a whole hell of a lot to do with Nazism and telling people what to do and killing [?], don’t you? [...] [Onstage in San Diego, CA, USA, January 27, 1992] |

Blackstar- ADMIN

- Posts : 13905

Plectra : 91359

Reputation : 101

Join date : 2018-03-17

Re: 1991.10.04 - L.A. Weekly - Guns N' Roses: Up From Nowhere

Re: 1991.10.04 - L.A. Weekly - Guns N' Roses: Up From Nowhere

Axl didn't get the reference so he misunderstood the analogy, which wasn't so unflattering:

https://film.avclub.com/our-hitler-a-film-from-germany-1798203697

This happens when writers use all their intellectual arsenal reviewing rock records to impress

https://film.avclub.com/our-hitler-a-film-from-germany-1798203697

This happens when writers use all their intellectual arsenal reviewing rock records to impress

Blackstar- ADMIN

- Posts : 13905

Plectra : 91359

Reputation : 101

Join date : 2018-03-17

Re: 1991.10.04 - L.A. Weekly - Guns N' Roses: Up From Nowhere

Re: 1991.10.04 - L.A. Weekly - Guns N' Roses: Up From Nowhere

Blackstar wrote:Axl didn't get the reference so he misunderstood the analogy, which wasn't so unflattering:

https://film.avclub.com/our-hitler-a-film-from-germany-1798203697

This happens when writers use all their intellectual arsenal reviewing rock records to impress

Haha, yes, I thought the review was pretty nice. Too bad he misunderstood.

Soulmonster- Band Lawyer

-

Posts : 15971

Plectra : 77388

Reputation : 830

Join date : 2010-07-06

Similar topics

Similar topics» 1991.08.09 - Entertainment Weekly - Guns N' Roses: Out of control

» 2002.12.13 - Entertainment Weekly - Are Guns N' Roses Over?

» 1988.01.15 - L.A. Weekly - Ad about show with Guns N' Roses members

» 1991.MM.DD - Sky - Guns N' Roses

» 2002.11.12 - Entertainment Weekly - Four ex-Guns -- N' no Roses -- Plan New CD (Slash)

» 2002.12.13 - Entertainment Weekly - Are Guns N' Roses Over?

» 1988.01.15 - L.A. Weekly - Ad about show with Guns N' Roses members

» 1991.MM.DD - Sky - Guns N' Roses

» 2002.11.12 - Entertainment Weekly - Four ex-Guns -- N' no Roses -- Plan New CD (Slash)

Page 1 of 1

Permissions in this forum:

You cannot reply to topics in this forum