2004.06.DD - Guitar Player - Straight Shooter (Slash)

Page 1 of 1

2004.06.DD - Guitar Player - Straight Shooter (Slash)

2004.06.DD - Guitar Player - Straight Shooter (Slash)

Thanks to @Surge for sending us this article!

--------------------------------------------------------

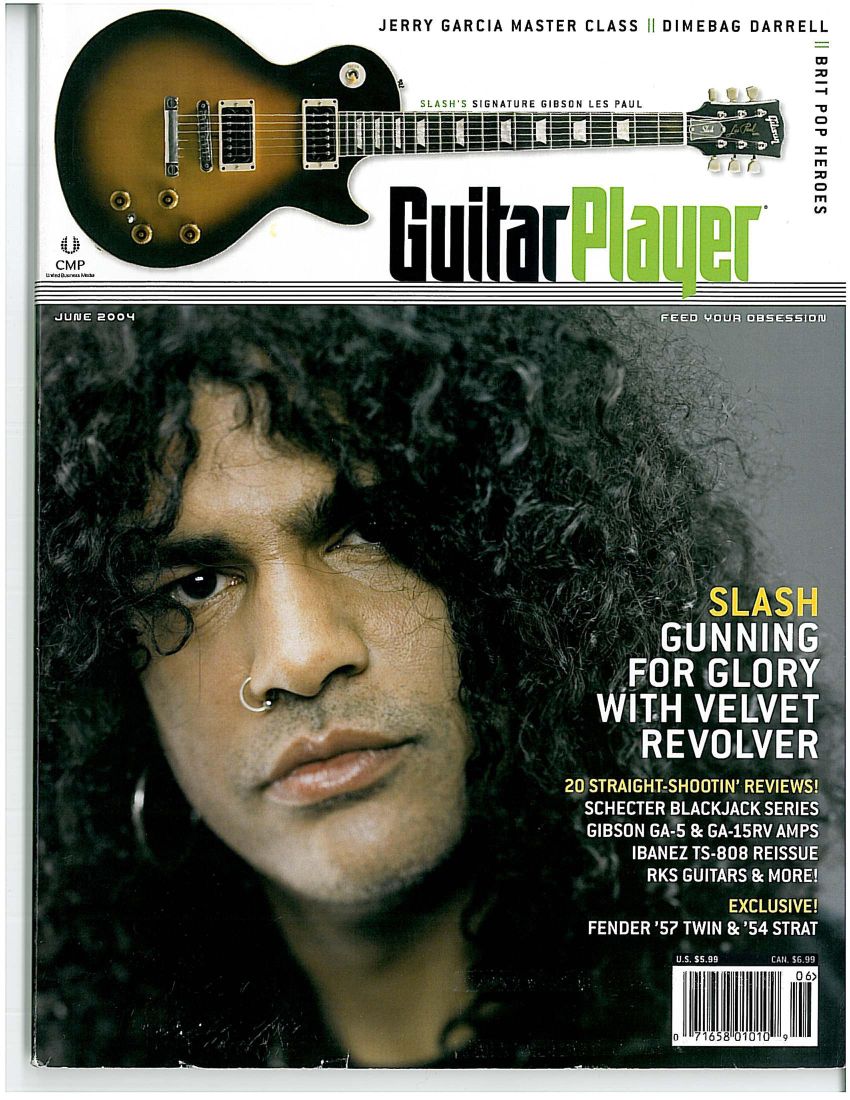

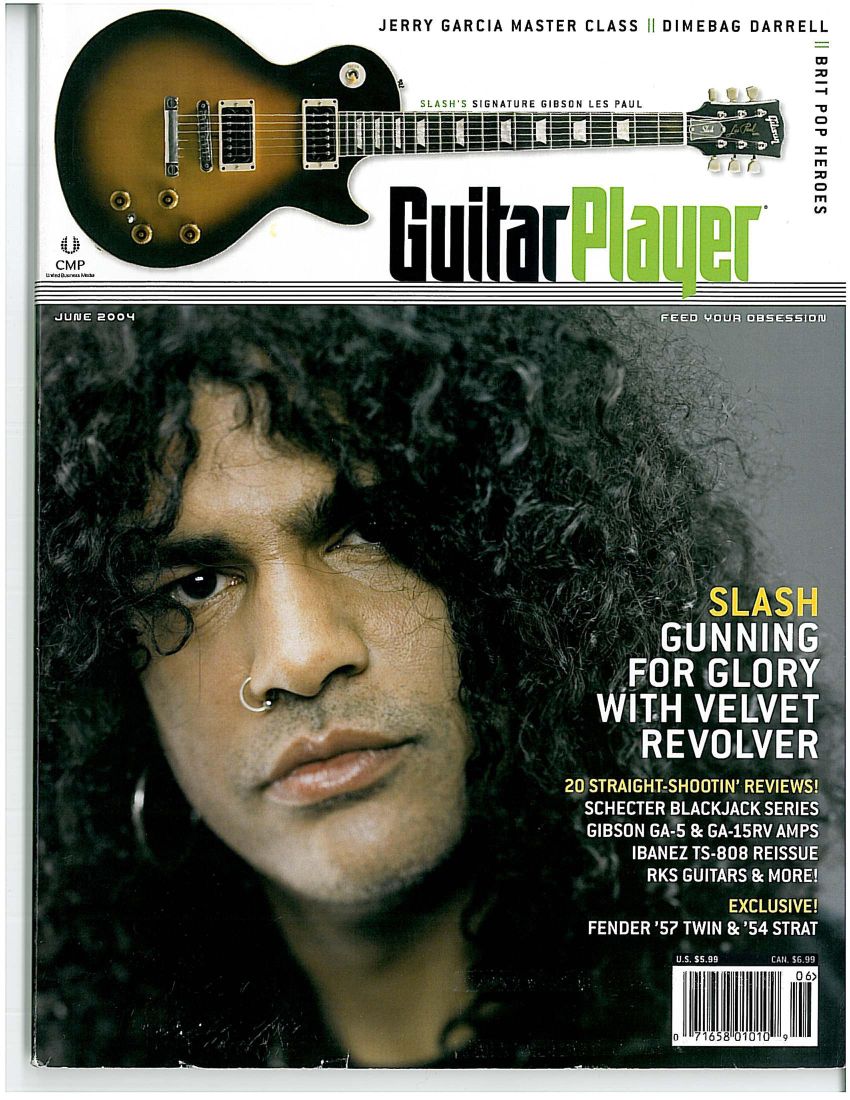

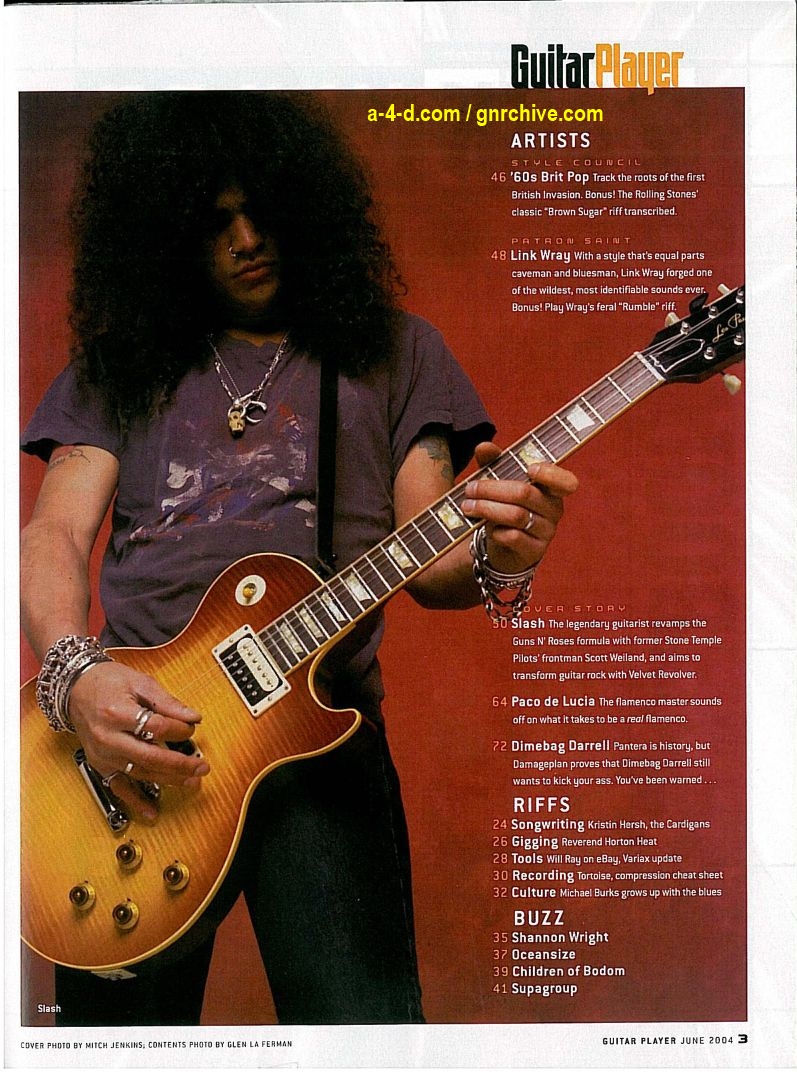

SLASH - GUNNING FOR GLORY WITH VELVET REVOLVER

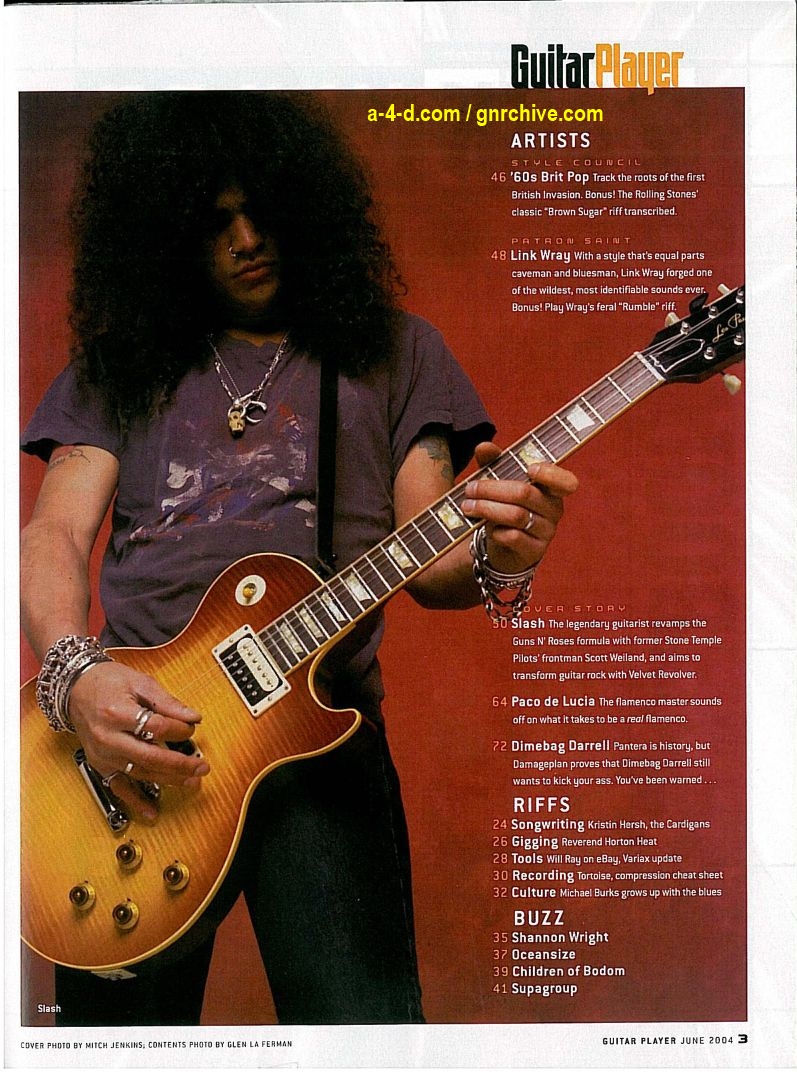

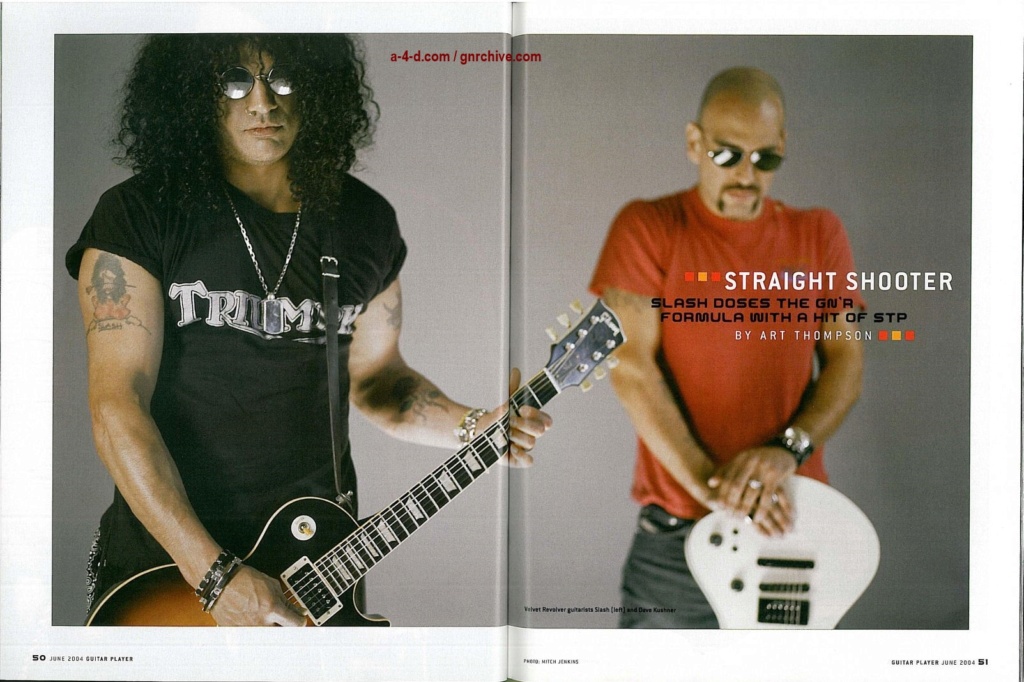

STRAIGHT SHOOTER

SLASH DOSES THE GN’R FORMULA WITH A HIT OF STP

BY ART THOMPSON

PHOTO CREDITS: MITCH JENKINS; GLEN LA FERMAN; KEN SETTLE; ANNAMARIA DI SANTO; MARTY TEMME; CHRISTINE KOHOUT KUSHNER

You know a guitarist has become golden when people refer to him as an icon of his respective genre – i.e. B.B. King for blues, Jerry Garcia for hippy rock, Jimi Hendrix for psychedelia, and so on. It’s a little simplistic, but sometimes an artist’s image, personality, and playing style are so definitive that their social and creative impact can hardly be acknowledged without using the “i” word.

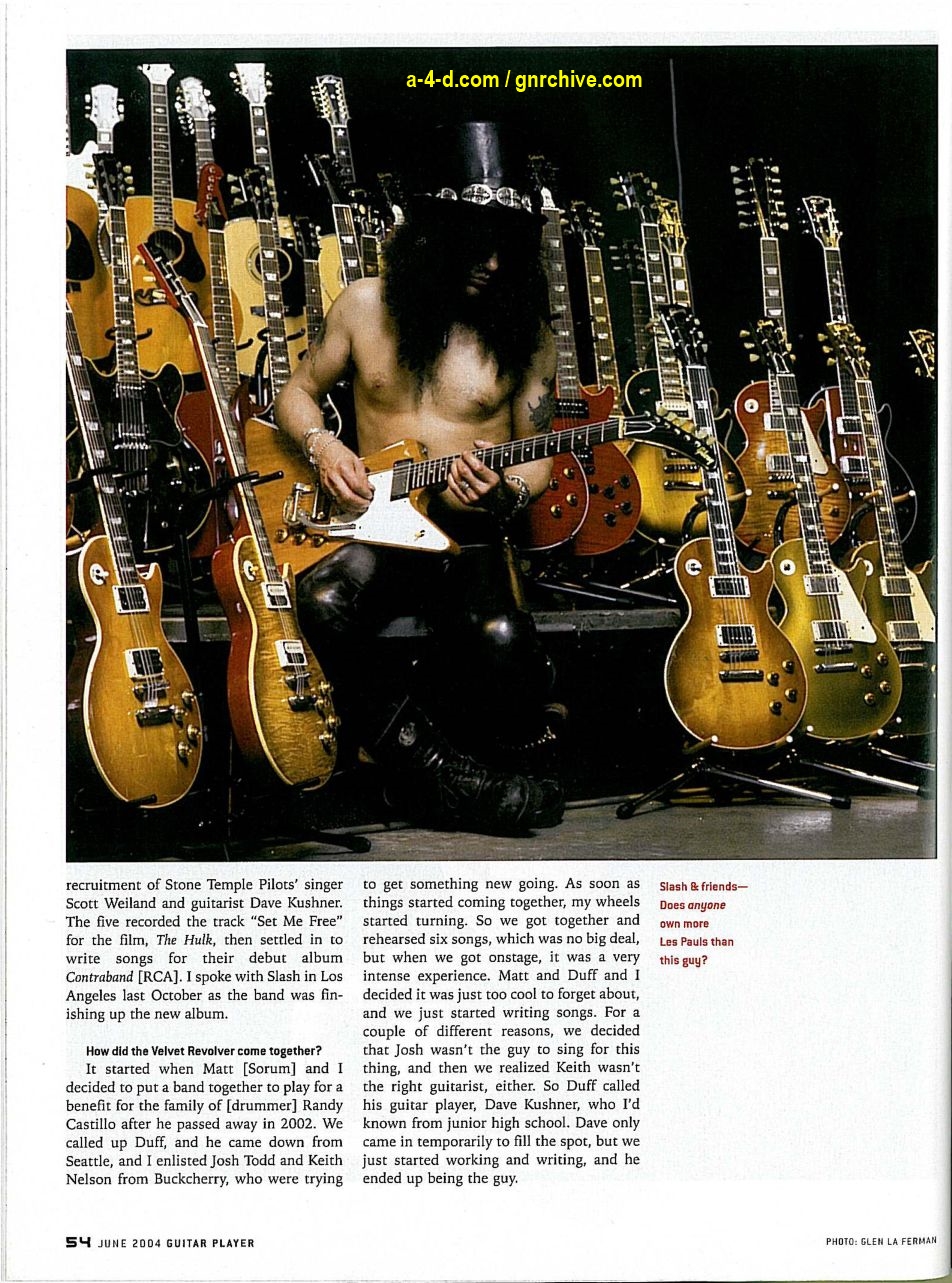

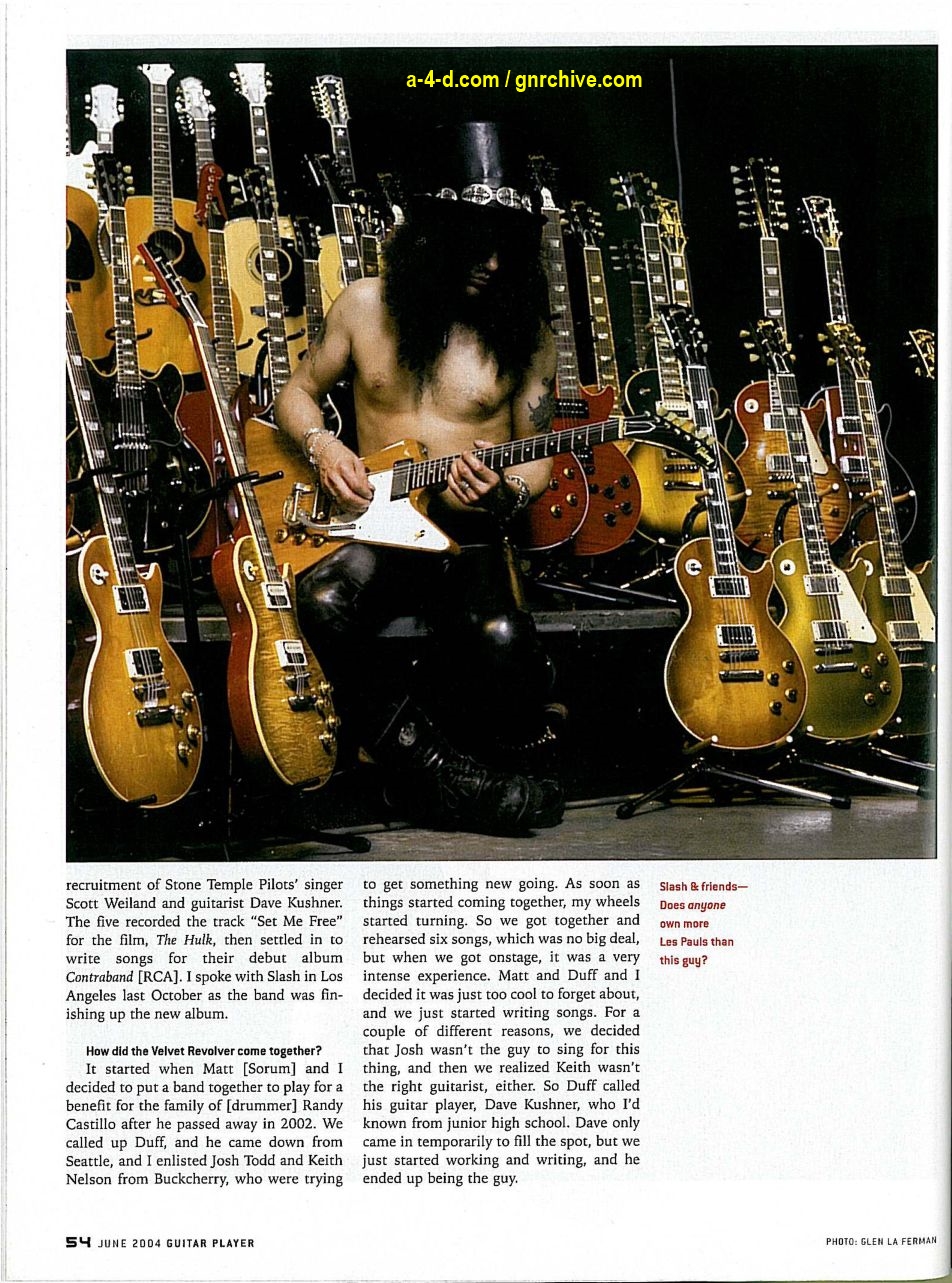

For example, who would debate calling Slash an icon? Following his rise to world-wide fame with Guns N’ Roses, Slash became a figurehead for a style of high-intensity rock that was defined by two GN’R masterpieces: “Welcome to the Jungle” and “Sweet Child O’ Mine.” Slash’s hard-ass riffs and searing tone invoke the glory of ‘70s arena rock, which had all but disappeared in the big hair/pointy guitar/Spandex ridiculousness of the ‘80s. Slash made it cool again to sling a Les Paul, and his bad-boy image was strong enough to live on in animated form in the recent TV series, Kid Notorious.

Of course, even an iconic musician has to figure out what to do when the success train runs out of steam, and Slash, being the restless animal he is, had already begun aiming his guitar in new directions as Guns’ creative ammo began to misfire. As the band’s trajectory started heading earthward, Slash pushed on with his Snakepit project, releasing It’s Five O’Clock Somewhere in 1995’s and – following his formal exit from GN’R in 1996, his subsequent Blues Ball project, and the creation of a fresh Snakepit lineup – Ain’t Life Grand in 2000.

Snakepit soon slithered away, but Slash kept his 6-string juices flowing by indulging in session work and guest appearances – even a sojourn into the smooth-jazz realm with his popular, flamenco-inspired “Obsession Confession.”

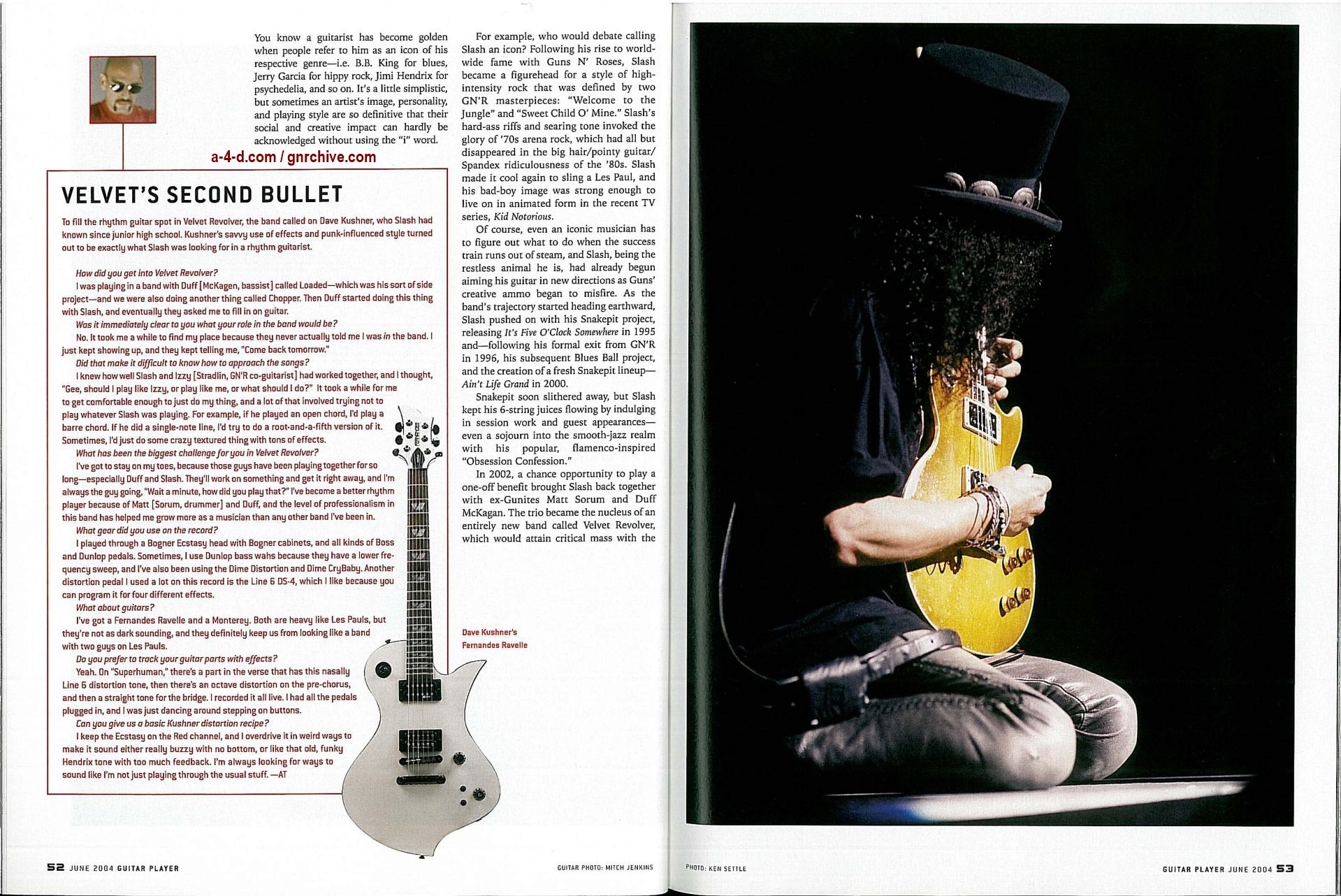

In 2002, a chance opportunity to play a one-off benefit brought Slash back together with ex-Gunites Matt Sorum and Duff McKagan. The trio became the nucleus of an entirely new band called Velvet Revolver, which would attain critical mass with the recruitment of Stone Temple Pilots’ singer Scott Weiland and guitarist Dave Kushner. The five recorded the track “Set Me Free” for the film, The Hulk, then settled in to write songs for their debut album Contraband (RCA). I spoke with Slash in Los Angeles last October as the band was finishing up the new album.

GP: How did the Velvet Revolver come together?

It started when Matt (Sorum) and I decided to put a band together to play for a benefit for the family of (drummer) Randy Castillo after he passed away in 2002. We called up Duff, and he came down from Seattle, and I enlisted Josh Todd and Keith Nelson from Buckcherry, who were trying to get something new going. As soon as things started coming together, my wheels started turning. So we got together and rehearsed six songs, which was no big deal, but when we got onstage, it was a very intense experience. Matt and Duff and I decided it was just too cool to forget about, and we just started writing songs. For a couple of different reasons, we decided that Josh wasn’t the guy to sing for this thing, and then we realized Keith wasn’t the right guitarist, either. So Duff called his guitar player, Dave Kushner, who I’d known from junior high school. Dave only came in temporarily to fill the spot, but we just started working and writing, and he ended up being the guy.

GP: How did you get Scott Weiland in the band?

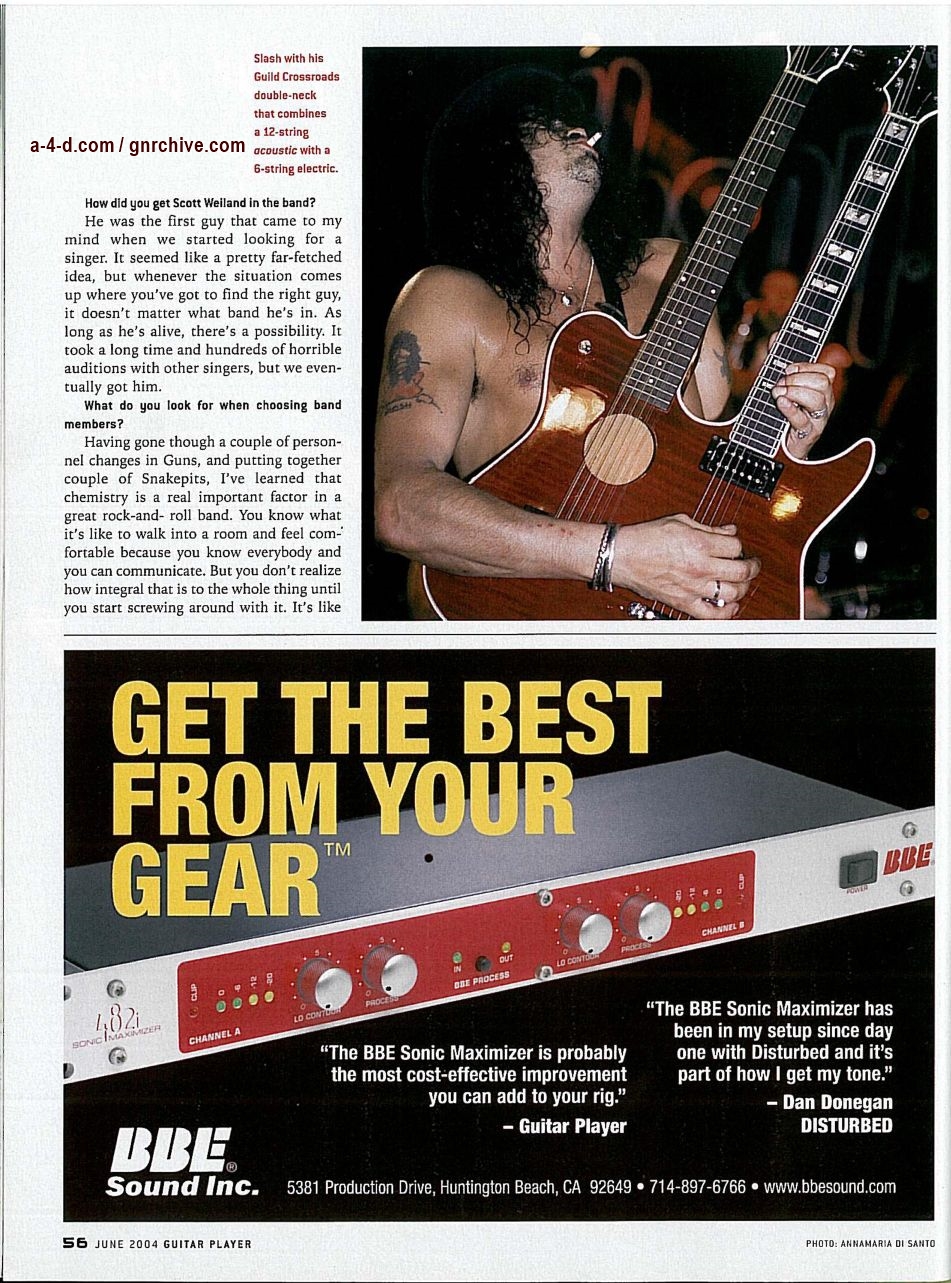

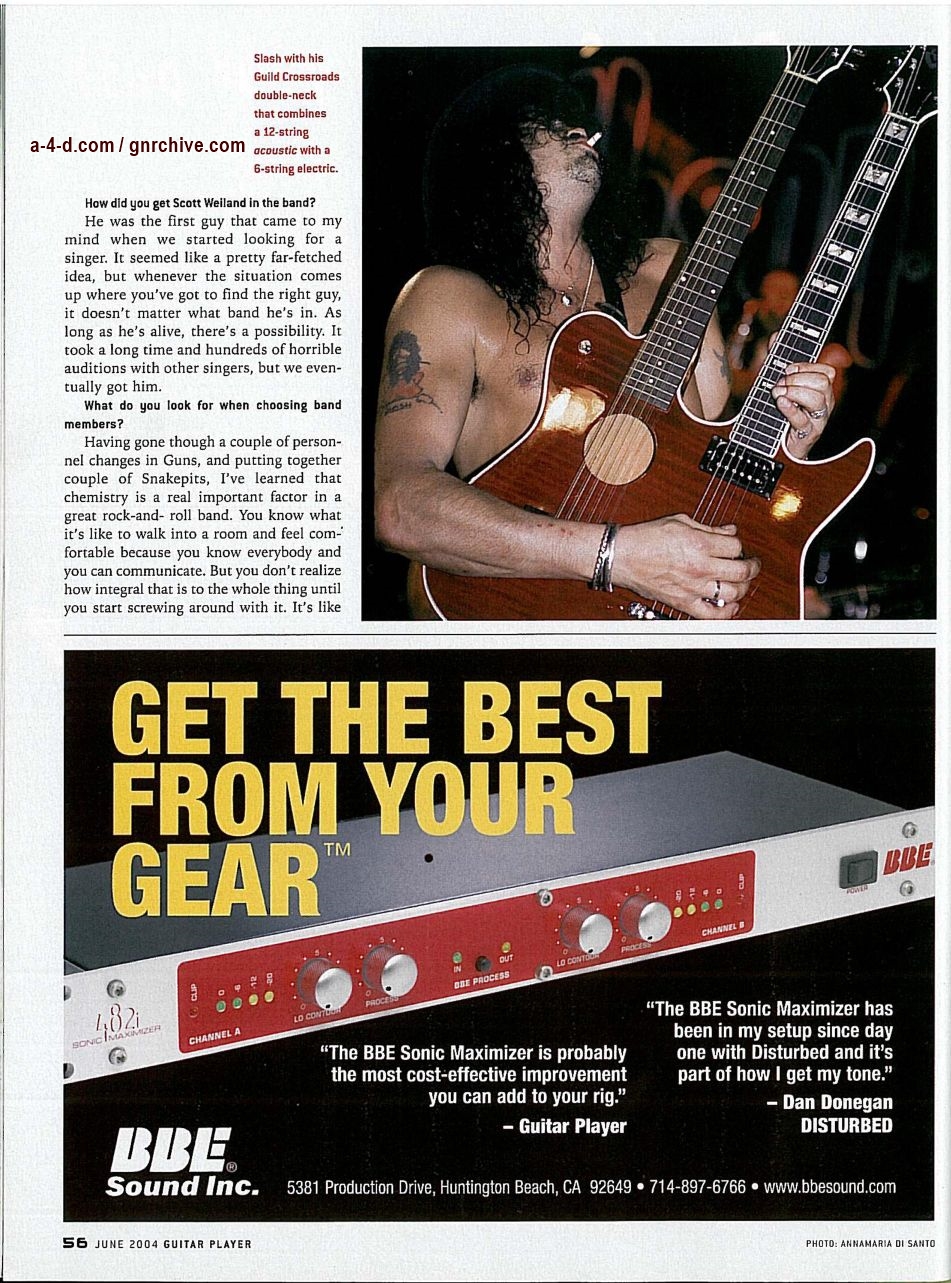

He was the first guy that came to my mind when we started looking for a singer. It seemed like a pretty far-fetched idea, but whenever the situation comes up where you’ve got to find the right guy, it doesn’t matter what band he’s in. As long as he’s alive, there’s a possibility. It took a long time and hundreds of horrible auditions with other singers, but we eventually got him.

GP: What do you look for when choosing band members?

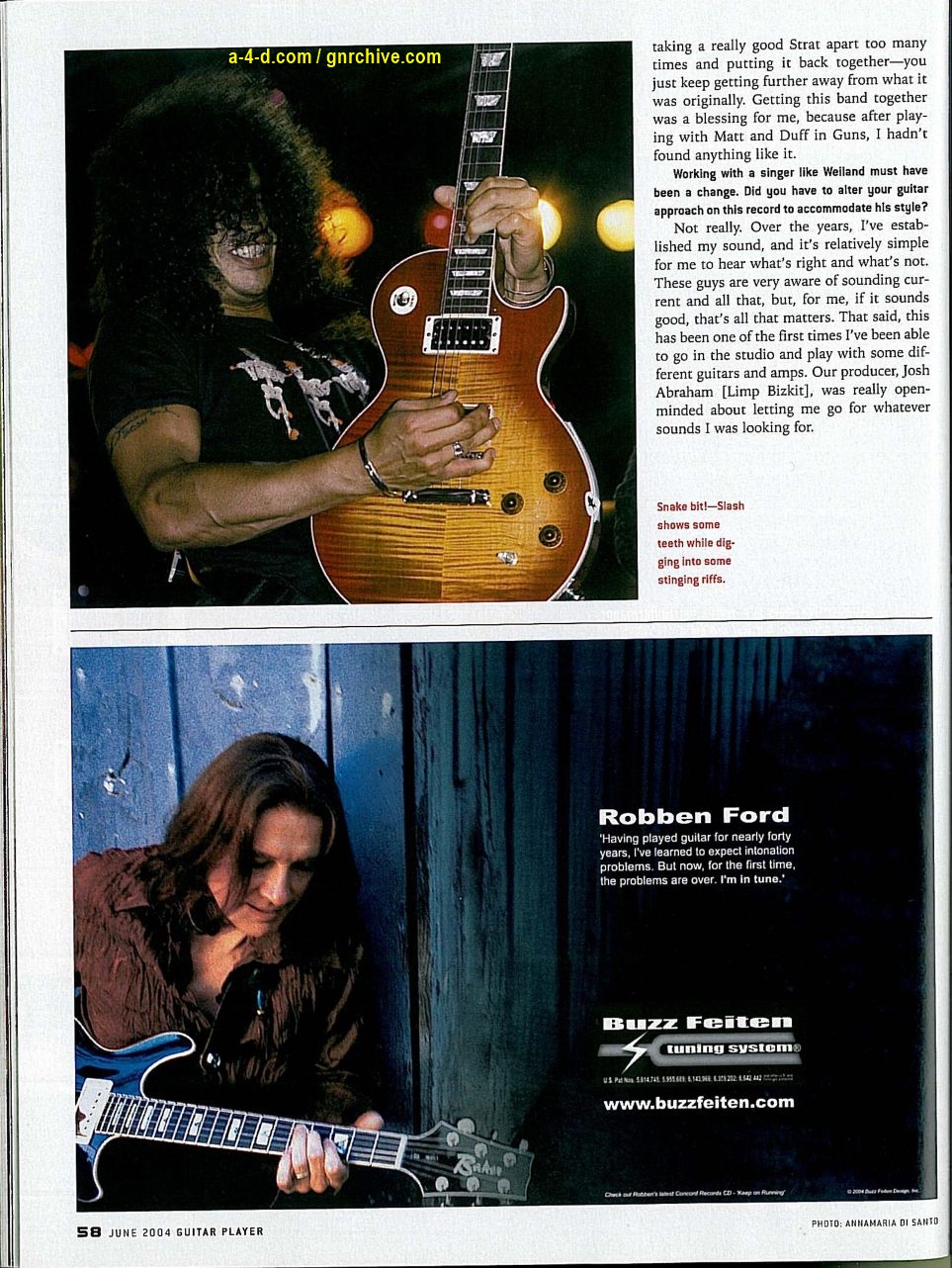

Having gone through a couple of personnel changes in Guns, and putting together couple of Snakepits, I’ve learned that chemistry is a real important factor in a great rock-and-roll band. You know what it’s like to walk into a room and feel comfortable because you know everybody and you can communicate. But you don’t realize how integral that is to the whole thing until you start screwing around with it. It’s like taking a really good Strat apart too many times and putting it back together – you just keep getting further away from what it was originally. Getting this band together was a blessing for me, because after playing with Matt and Duff in Guns, I hadn’t found anything like it.

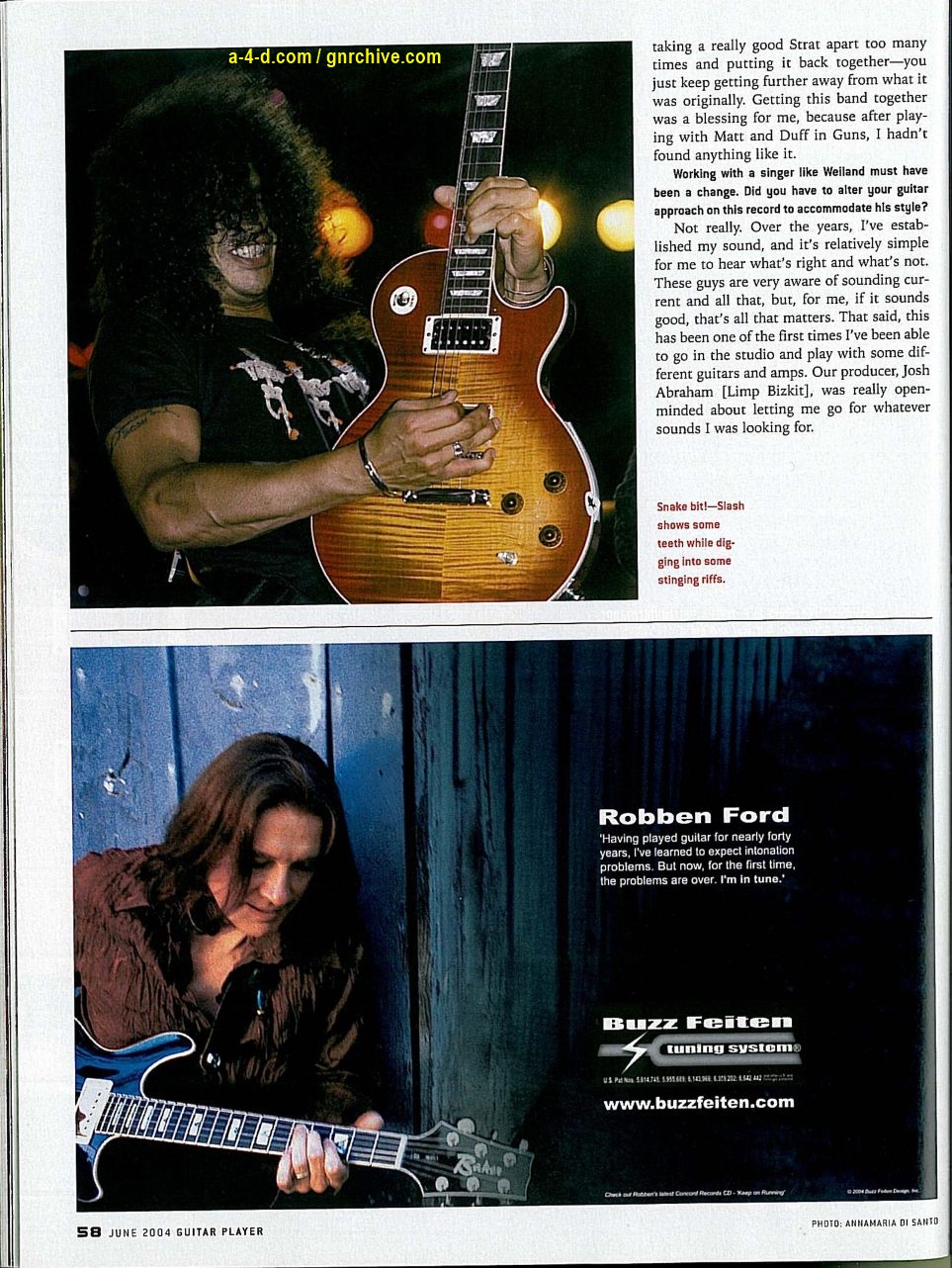

GP: Working with a singer like Weiland must have been a change. Did you have to alter your guitar approach on this record to accommodate his style?

Not really. Over the years, I’ve established my sound, and it’s relatively simple for me to hear what’s right and what’s not. These guys are very aware of sounding current and all that, but, for me, if it sounds good, that’s all that matters. That said, this has been one of the first times I’ve been able to go in the studio and play with some different guitars and amps. Our producer, Josh Abraham (Limp Bizkit), was really open-minded about letting me go for whatever sounds I was looking for.

GP: Can you give us some examples?

On one song, there’s a Tele that’s blowing through the roof with distortion, and it’s combined with a baritone guitar. Those two guitars sound amazing together! On the same song, I also used a Strat, and that’s really different for me. I think the main thing was just getting different amp sounds. I used a Vox AC30 for the first time along with my Marshalls, and that’s something I’ve never done before. We also had a lot of little Fender amps in the studio that we’d push with different pedals for oddball sounds. I wanted to give some character to the new songs, but if I only heard the Marshall and my Les Paul on something, that’s all I’d use.

GP: Have you felt fenced-in by producers in that regard?

It’s not so much about being fenced-in, but I get intimated by schedules. For example, I did a session with Eddie Kramer for a kids’ record called Sing a Song for Six Pence. All these different guitar players were on it, and I went in and just used what was there in the studio at the time – a Les Paul and a Line 6 amp. I’ve very conscious of taking up too much time when I’m playing on someone else’s record, so I try to blaze through things quickly and not get too hung up about sounds.

GP: But you’re not that way when working on your own records?

Well, when we were doing Use Your Illusion for Guns, I used a lot of different equipment, though, for some reason, it doesn’t sound like it. I had a few different guitars going, but I think it was pretty much my basic amp setup. This time, I had access to a lot of different amps, and I actually had sounds in mind that I thought would be cool. So it worked out a little differently because I felt relaxed enough to do whatever I wanted.

GP: Do you prefer tracking to tape?

Yeah. I think that most people who are concerned with sonics prefer to hear that girthy thing that tape provides. You can hear the absence of groove and vibe on records that are made entirely on Pro Tools only because it makes it easier to do overdubs. We didn’t do any Pro Tools editing, though. We made sure we had our stuff together before we started tracking. Some things are sacred, and one is having the ability to just play the damn song.

GP: How do you track your overdubs?

I like to create as live an experience as possible, so I’ll stand in front of the monitors in the control room with a subwoofer that makes the floor move a little bit.

GP: Can you describe the songwriting process for Contraband?

Everything was driven by a riff that one of us came up with. Then we started putting ideas together until we had a beginning, a middle, and an end. When Scott came in, the process changed somewhat because we started jamming more and letting Scot decide if he felt inspired to sing something to what we were playing.

GP: Are the guitar parts developed in the same collaborative way?

Yeah. “Set Me Free” actually started with something Matt came up with on guitar. It was very basic, but sometimes the best way for me to write is to expand on someone’s very sparse idea, because it’ll inspire things I wouldn’t write myself. In this case, it was all these different ideas for chord voicings throughout the chorus. Then there’s the stuff where I came up with a riff and maybe a verse, and, of course, it all changed once the guys put their tag on it.

GP: Are you pretty quick about coming up with solos?

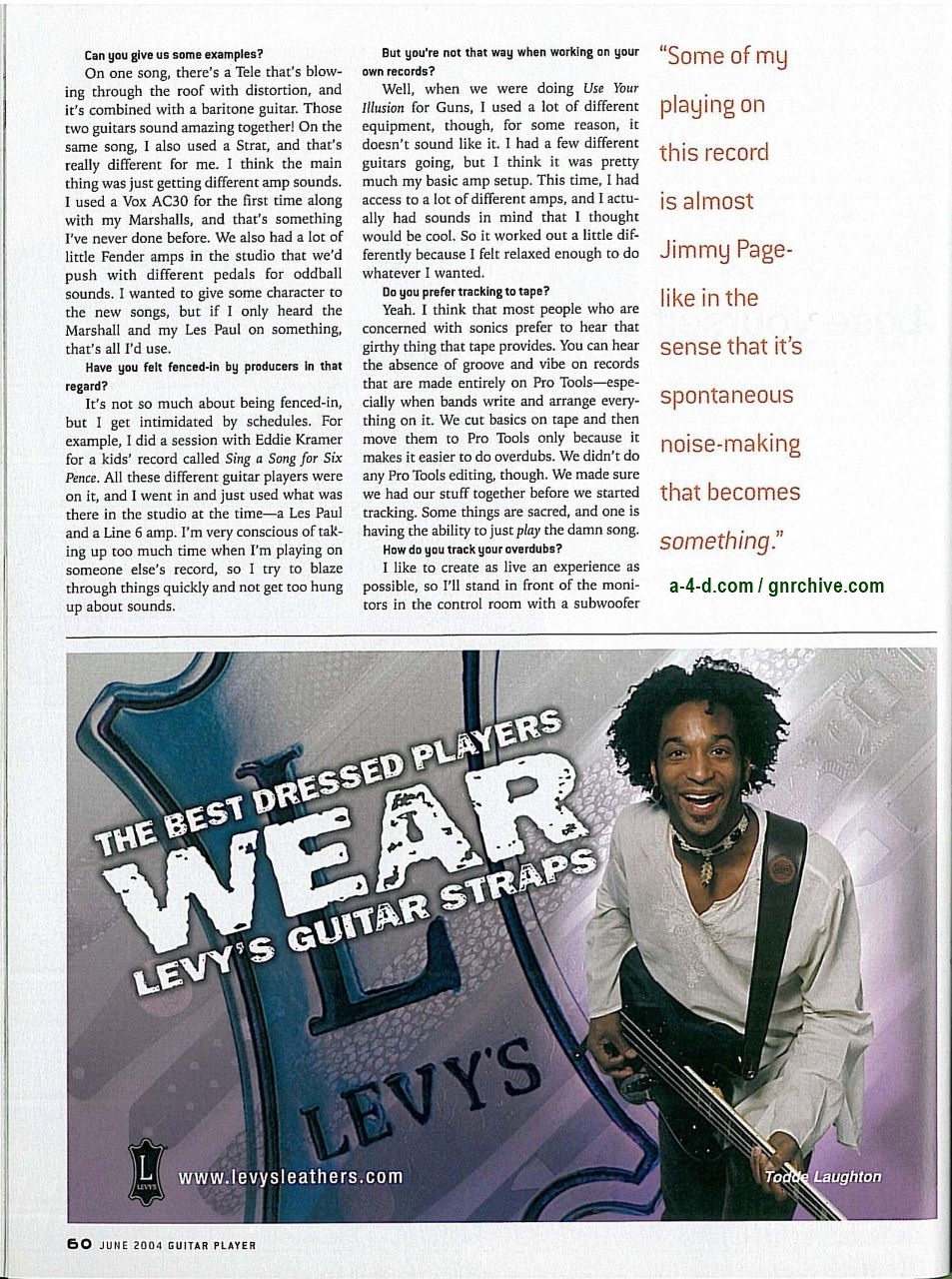

I’m a little more focused now, and I think I’ve become more calm about listening to what I’m doing. Maybe it’s just experience. A lot of the solos on this record are very spontaneous. Some of my playing is almost Jimmy Page-like in the sense that it’s like making noise that becomes something.

GP: Will you try to duplicate those solos live?

That’s sort of tricky, because the more you play something, the easier it is to understand where the notes fall, and then you become meticulous about it. I try not to do that. I’ve found that you can play a basically improvised solo, but structure it so that the key notes land on certain parts of the beat – that way it still sounds spontaneous.

GP: How does working with Dave compare to working with Izzy (Stradlin)?

Izzy and I had a simple, unsaid agreement: I’m in my world, he’s in his, and we’ll work on the same song together using completely different approaches. Dave is a little more similar in style to me, but he uses more effects. So he has his own trip, too. It’s almost the same in a way. If there’s something we’re doubling up on, we’ll work on it to try and come up with something a little more interesting. And we still do it from across the room.

GP: Are there certain guitarists you find particularly inspiring?

Steve Lukather and I are friends, and he never ceases to amaze me as to what you can do on guitar. We jammed at a blues bar recently, and where my way of doing things in that situation is taking a Bic lighter and using it as a slide, his is finding all the different possibilities of a I-IV-V progression. It blows my mind, because I really don’t know much about that stuff. Jeff Beck is another guy who never ceases to amaze me – even when he’s just screwing around! I’ve played with Jeff a few times and it has always been cool.

GP: What has been the toughest thing you’ve done?

I played with Ray Charles and his orchestra a couple of times in the studio recently. They were making a movie, and they needed to recreate a recording session. So they handed me these chord charts, and, man, one was a real up-tempo thing that was quite challenging. I’m playing with these guys who have played these songs a million times, and they don’t like to screw around. I don’t read music – the best I can do is a chord chart – so that was an experience. Ray was easy on me, but I saw how he would come down on his band members for screwing up.

GP: Between your high-profile gigs, you’ve always kept working. What drives you?

I’m scared I’m going to forget how to do it! I realize I’m still learning, and I guess I’m a bit paranoid about maintaining my chops. I need to play in front of audiences to keep my spirit up, and I need to do sessions in order to force myself to learn new things. But the bottom line is, I just can’t stand sitting around and doing nothing.

***

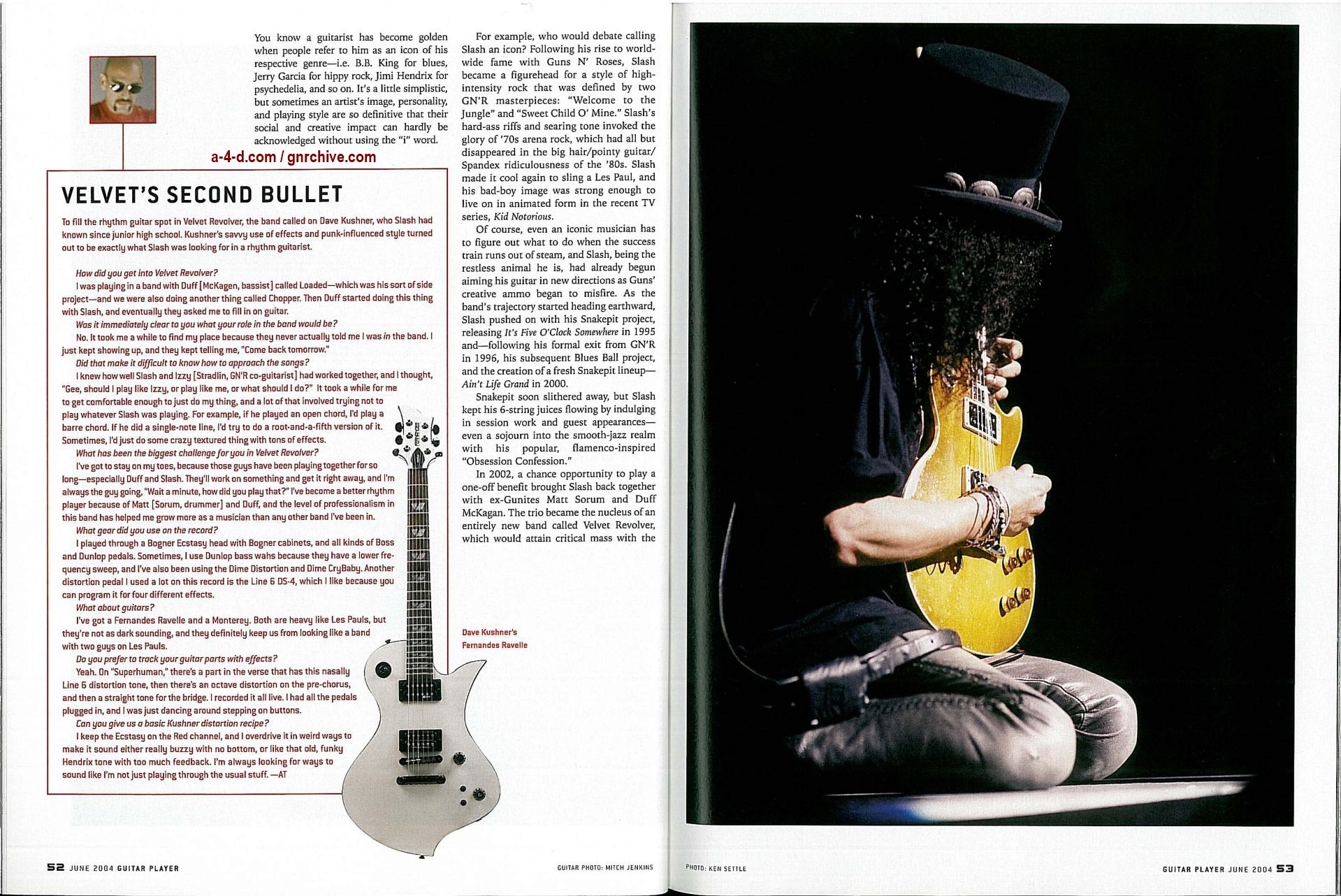

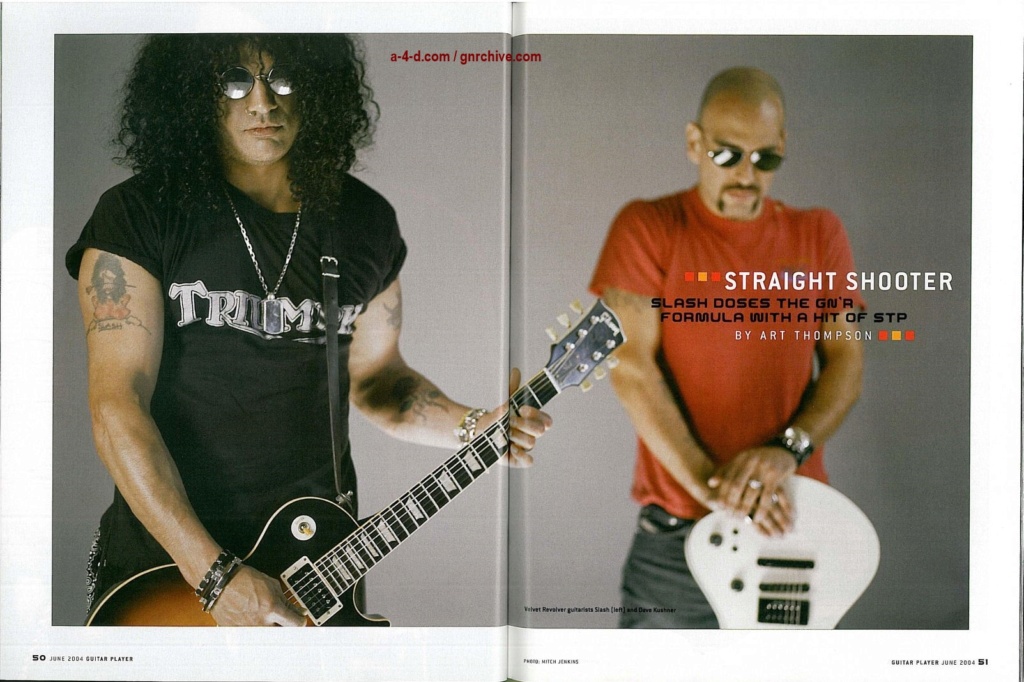

VELVET’S SECOND BULLET

To fill the rhythm guitar spot in Velvet Revolver, the band called on Dave Kushner, who Slash had known since junior high school. Kushner’s savvy use of effects and punk-influenced style turned out to be exactly what Slash was looking for in a rhythm guitarist.

GP: How did you get into Velvet Revolver?

I was playing in a band with Duff (McKagan, bassist) called Loaded – which was his sort of side project – and we were also doing another thing called Chopper. Then Duff started doing this thing with Slash, and eventually they asked me to fill in on guitar.

GP: Was it immediately clear to you what your role in the band would be?

No. It took me a while to find my place because they never actually told me I was in the band. I just kept showing up, and they kept telling me, “Come back tomorrow.”

GP: Did that make it difficult to know how to approach the songs?

I knew how well Slash and Izzy (Stradlin, GN’R co-guitarist) had worked together, and I thought, “Gee, should I play like Izzy, or play like me, or what should I do?” It took a while for me to get comfortable enough to just do my thing, and a lot of that involved trying not to play whatever Slash was playing. For example, if he played an open chord, I’d play a barre chord. If he did a single-note line, I’d try to do a root-and-a-fifth version of it. Sometimes, I’d just do some crazy textured thing with tons of effects.

GP: What has been the biggest challenge for you in Velvet Revolver?

I’ve got to stay on my toes, because those guys have been playing together for so long – especially Duff and Slash. They’ll work on something and get it right away, and I’m always the guy going, “Wait a minute, how did you play that?” I’ve become a better rhythm player because of Matt (Sorum, drummer) and Duff, and the level of professionalism in this band has helped me grow more as a musician than any other band I’ve been in.

GP: What gear did you use on the record?

I played through a Bogner Ecstasy head with Bogner cabinets, and all kinds of Boss and Dunlop pedals. Sometimes, I use Dunlop bass wahs because they have a lower frequency sweep, and I’ve also been using the Dime Distortion and Dime CryBaby. Another distortion pedal I used a lot on this record is the Line 6 DS-4, which I like because you can program it for four different effects.

GP: What about guitars?

I’ve got a Fernandes Ravelle and a Monterey. Both are heavy like Les Pauls, but they’re not as dark sounding, and they definitely keep us from looking like a band with two guys on Les Pauls.

GP: Do you prefer to track your guitar parts with effects?

Yeah. On “Superhuman,” there’s a part in the verse that has this nasally Line 6 distortion tone, then there’s an octave distortion of the pre-chorus, and then a straight tone for the bridge. I recorded it all live. I had all the pedals plugged in, and I was just dancing around stepping on buttons.

GP: Can you give us a basic Kushner distortion recipe?

I keep the Ecstasy on the Red channel, and I overdrive it in weird ways to make it sound either really buzzy with no bottom, or like that old, funky Hendrix tone with too much feedback. I’m always looking for ways to sound like I’m not just playing through the usual stuff. – AT

--------------------------------------------------------

SLASH - GUNNING FOR GLORY WITH VELVET REVOLVER

STRAIGHT SHOOTER

SLASH DOSES THE GN’R FORMULA WITH A HIT OF STP

BY ART THOMPSON

PHOTO CREDITS: MITCH JENKINS; GLEN LA FERMAN; KEN SETTLE; ANNAMARIA DI SANTO; MARTY TEMME; CHRISTINE KOHOUT KUSHNER

You know a guitarist has become golden when people refer to him as an icon of his respective genre – i.e. B.B. King for blues, Jerry Garcia for hippy rock, Jimi Hendrix for psychedelia, and so on. It’s a little simplistic, but sometimes an artist’s image, personality, and playing style are so definitive that their social and creative impact can hardly be acknowledged without using the “i” word.

For example, who would debate calling Slash an icon? Following his rise to world-wide fame with Guns N’ Roses, Slash became a figurehead for a style of high-intensity rock that was defined by two GN’R masterpieces: “Welcome to the Jungle” and “Sweet Child O’ Mine.” Slash’s hard-ass riffs and searing tone invoke the glory of ‘70s arena rock, which had all but disappeared in the big hair/pointy guitar/Spandex ridiculousness of the ‘80s. Slash made it cool again to sling a Les Paul, and his bad-boy image was strong enough to live on in animated form in the recent TV series, Kid Notorious.

Of course, even an iconic musician has to figure out what to do when the success train runs out of steam, and Slash, being the restless animal he is, had already begun aiming his guitar in new directions as Guns’ creative ammo began to misfire. As the band’s trajectory started heading earthward, Slash pushed on with his Snakepit project, releasing It’s Five O’Clock Somewhere in 1995’s and – following his formal exit from GN’R in 1996, his subsequent Blues Ball project, and the creation of a fresh Snakepit lineup – Ain’t Life Grand in 2000.

Snakepit soon slithered away, but Slash kept his 6-string juices flowing by indulging in session work and guest appearances – even a sojourn into the smooth-jazz realm with his popular, flamenco-inspired “Obsession Confession.”

In 2002, a chance opportunity to play a one-off benefit brought Slash back together with ex-Gunites Matt Sorum and Duff McKagan. The trio became the nucleus of an entirely new band called Velvet Revolver, which would attain critical mass with the recruitment of Stone Temple Pilots’ singer Scott Weiland and guitarist Dave Kushner. The five recorded the track “Set Me Free” for the film, The Hulk, then settled in to write songs for their debut album Contraband (RCA). I spoke with Slash in Los Angeles last October as the band was finishing up the new album.

GP: How did the Velvet Revolver come together?

It started when Matt (Sorum) and I decided to put a band together to play for a benefit for the family of (drummer) Randy Castillo after he passed away in 2002. We called up Duff, and he came down from Seattle, and I enlisted Josh Todd and Keith Nelson from Buckcherry, who were trying to get something new going. As soon as things started coming together, my wheels started turning. So we got together and rehearsed six songs, which was no big deal, but when we got onstage, it was a very intense experience. Matt and Duff and I decided it was just too cool to forget about, and we just started writing songs. For a couple of different reasons, we decided that Josh wasn’t the guy to sing for this thing, and then we realized Keith wasn’t the right guitarist, either. So Duff called his guitar player, Dave Kushner, who I’d known from junior high school. Dave only came in temporarily to fill the spot, but we just started working and writing, and he ended up being the guy.

GP: How did you get Scott Weiland in the band?

He was the first guy that came to my mind when we started looking for a singer. It seemed like a pretty far-fetched idea, but whenever the situation comes up where you’ve got to find the right guy, it doesn’t matter what band he’s in. As long as he’s alive, there’s a possibility. It took a long time and hundreds of horrible auditions with other singers, but we eventually got him.

GP: What do you look for when choosing band members?

Having gone through a couple of personnel changes in Guns, and putting together couple of Snakepits, I’ve learned that chemistry is a real important factor in a great rock-and-roll band. You know what it’s like to walk into a room and feel comfortable because you know everybody and you can communicate. But you don’t realize how integral that is to the whole thing until you start screwing around with it. It’s like taking a really good Strat apart too many times and putting it back together – you just keep getting further away from what it was originally. Getting this band together was a blessing for me, because after playing with Matt and Duff in Guns, I hadn’t found anything like it.

GP: Working with a singer like Weiland must have been a change. Did you have to alter your guitar approach on this record to accommodate his style?

Not really. Over the years, I’ve established my sound, and it’s relatively simple for me to hear what’s right and what’s not. These guys are very aware of sounding current and all that, but, for me, if it sounds good, that’s all that matters. That said, this has been one of the first times I’ve been able to go in the studio and play with some different guitars and amps. Our producer, Josh Abraham (Limp Bizkit), was really open-minded about letting me go for whatever sounds I was looking for.

GP: Can you give us some examples?

On one song, there’s a Tele that’s blowing through the roof with distortion, and it’s combined with a baritone guitar. Those two guitars sound amazing together! On the same song, I also used a Strat, and that’s really different for me. I think the main thing was just getting different amp sounds. I used a Vox AC30 for the first time along with my Marshalls, and that’s something I’ve never done before. We also had a lot of little Fender amps in the studio that we’d push with different pedals for oddball sounds. I wanted to give some character to the new songs, but if I only heard the Marshall and my Les Paul on something, that’s all I’d use.

GP: Have you felt fenced-in by producers in that regard?

It’s not so much about being fenced-in, but I get intimated by schedules. For example, I did a session with Eddie Kramer for a kids’ record called Sing a Song for Six Pence. All these different guitar players were on it, and I went in and just used what was there in the studio at the time – a Les Paul and a Line 6 amp. I’ve very conscious of taking up too much time when I’m playing on someone else’s record, so I try to blaze through things quickly and not get too hung up about sounds.

GP: But you’re not that way when working on your own records?

Well, when we were doing Use Your Illusion for Guns, I used a lot of different equipment, though, for some reason, it doesn’t sound like it. I had a few different guitars going, but I think it was pretty much my basic amp setup. This time, I had access to a lot of different amps, and I actually had sounds in mind that I thought would be cool. So it worked out a little differently because I felt relaxed enough to do whatever I wanted.

GP: Do you prefer tracking to tape?

Yeah. I think that most people who are concerned with sonics prefer to hear that girthy thing that tape provides. You can hear the absence of groove and vibe on records that are made entirely on Pro Tools only because it makes it easier to do overdubs. We didn’t do any Pro Tools editing, though. We made sure we had our stuff together before we started tracking. Some things are sacred, and one is having the ability to just play the damn song.

GP: How do you track your overdubs?

I like to create as live an experience as possible, so I’ll stand in front of the monitors in the control room with a subwoofer that makes the floor move a little bit.

GP: Can you describe the songwriting process for Contraband?

Everything was driven by a riff that one of us came up with. Then we started putting ideas together until we had a beginning, a middle, and an end. When Scott came in, the process changed somewhat because we started jamming more and letting Scot decide if he felt inspired to sing something to what we were playing.

GP: Are the guitar parts developed in the same collaborative way?

Yeah. “Set Me Free” actually started with something Matt came up with on guitar. It was very basic, but sometimes the best way for me to write is to expand on someone’s very sparse idea, because it’ll inspire things I wouldn’t write myself. In this case, it was all these different ideas for chord voicings throughout the chorus. Then there’s the stuff where I came up with a riff and maybe a verse, and, of course, it all changed once the guys put their tag on it.

GP: Are you pretty quick about coming up with solos?

I’m a little more focused now, and I think I’ve become more calm about listening to what I’m doing. Maybe it’s just experience. A lot of the solos on this record are very spontaneous. Some of my playing is almost Jimmy Page-like in the sense that it’s like making noise that becomes something.

GP: Will you try to duplicate those solos live?

That’s sort of tricky, because the more you play something, the easier it is to understand where the notes fall, and then you become meticulous about it. I try not to do that. I’ve found that you can play a basically improvised solo, but structure it so that the key notes land on certain parts of the beat – that way it still sounds spontaneous.

GP: How does working with Dave compare to working with Izzy (Stradlin)?

Izzy and I had a simple, unsaid agreement: I’m in my world, he’s in his, and we’ll work on the same song together using completely different approaches. Dave is a little more similar in style to me, but he uses more effects. So he has his own trip, too. It’s almost the same in a way. If there’s something we’re doubling up on, we’ll work on it to try and come up with something a little more interesting. And we still do it from across the room.

GP: Are there certain guitarists you find particularly inspiring?

Steve Lukather and I are friends, and he never ceases to amaze me as to what you can do on guitar. We jammed at a blues bar recently, and where my way of doing things in that situation is taking a Bic lighter and using it as a slide, his is finding all the different possibilities of a I-IV-V progression. It blows my mind, because I really don’t know much about that stuff. Jeff Beck is another guy who never ceases to amaze me – even when he’s just screwing around! I’ve played with Jeff a few times and it has always been cool.

GP: What has been the toughest thing you’ve done?

I played with Ray Charles and his orchestra a couple of times in the studio recently. They were making a movie, and they needed to recreate a recording session. So they handed me these chord charts, and, man, one was a real up-tempo thing that was quite challenging. I’m playing with these guys who have played these songs a million times, and they don’t like to screw around. I don’t read music – the best I can do is a chord chart – so that was an experience. Ray was easy on me, but I saw how he would come down on his band members for screwing up.

GP: Between your high-profile gigs, you’ve always kept working. What drives you?

I’m scared I’m going to forget how to do it! I realize I’m still learning, and I guess I’m a bit paranoid about maintaining my chops. I need to play in front of audiences to keep my spirit up, and I need to do sessions in order to force myself to learn new things. But the bottom line is, I just can’t stand sitting around and doing nothing.

***

VELVET’S SECOND BULLET

To fill the rhythm guitar spot in Velvet Revolver, the band called on Dave Kushner, who Slash had known since junior high school. Kushner’s savvy use of effects and punk-influenced style turned out to be exactly what Slash was looking for in a rhythm guitarist.

GP: How did you get into Velvet Revolver?

I was playing in a band with Duff (McKagan, bassist) called Loaded – which was his sort of side project – and we were also doing another thing called Chopper. Then Duff started doing this thing with Slash, and eventually they asked me to fill in on guitar.

GP: Was it immediately clear to you what your role in the band would be?

No. It took me a while to find my place because they never actually told me I was in the band. I just kept showing up, and they kept telling me, “Come back tomorrow.”

GP: Did that make it difficult to know how to approach the songs?

I knew how well Slash and Izzy (Stradlin, GN’R co-guitarist) had worked together, and I thought, “Gee, should I play like Izzy, or play like me, or what should I do?” It took a while for me to get comfortable enough to just do my thing, and a lot of that involved trying not to play whatever Slash was playing. For example, if he played an open chord, I’d play a barre chord. If he did a single-note line, I’d try to do a root-and-a-fifth version of it. Sometimes, I’d just do some crazy textured thing with tons of effects.

GP: What has been the biggest challenge for you in Velvet Revolver?

I’ve got to stay on my toes, because those guys have been playing together for so long – especially Duff and Slash. They’ll work on something and get it right away, and I’m always the guy going, “Wait a minute, how did you play that?” I’ve become a better rhythm player because of Matt (Sorum, drummer) and Duff, and the level of professionalism in this band has helped me grow more as a musician than any other band I’ve been in.

GP: What gear did you use on the record?

I played through a Bogner Ecstasy head with Bogner cabinets, and all kinds of Boss and Dunlop pedals. Sometimes, I use Dunlop bass wahs because they have a lower frequency sweep, and I’ve also been using the Dime Distortion and Dime CryBaby. Another distortion pedal I used a lot on this record is the Line 6 DS-4, which I like because you can program it for four different effects.

GP: What about guitars?

I’ve got a Fernandes Ravelle and a Monterey. Both are heavy like Les Pauls, but they’re not as dark sounding, and they definitely keep us from looking like a band with two guys on Les Pauls.

GP: Do you prefer to track your guitar parts with effects?

Yeah. On “Superhuman,” there’s a part in the verse that has this nasally Line 6 distortion tone, then there’s an octave distortion of the pre-chorus, and then a straight tone for the bridge. I recorded it all live. I had all the pedals plugged in, and I was just dancing around stepping on buttons.

GP: Can you give us a basic Kushner distortion recipe?

I keep the Ecstasy on the Red channel, and I overdrive it in weird ways to make it sound either really buzzy with no bottom, or like that old, funky Hendrix tone with too much feedback. I’m always looking for ways to sound like I’m not just playing through the usual stuff. – AT

Blackstar- ADMIN

- Posts : 13902

Plectra : 91332

Reputation : 101

Join date : 2018-03-17

Similar topics

Similar topics» 2008.06.DD - Guitar Player - Hustle & Flow (Slash)

» 2019.04.05 - Guitar.com - “I’m still a self-conscious and insecure guitar player!” (Slash)

» 2004.12.DD - Hit Parader - Straight Aim (Slash, Duff)

» 2000.12.DD - Guitar Player - Slash & Burn (Slash)

» 2023.05.DD - Guitar Player - Slash: The Collection

» 2019.04.05 - Guitar.com - “I’m still a self-conscious and insecure guitar player!” (Slash)

» 2004.12.DD - Hit Parader - Straight Aim (Slash, Duff)

» 2000.12.DD - Guitar Player - Slash & Burn (Slash)

» 2023.05.DD - Guitar Player - Slash: The Collection

Page 1 of 1

Permissions in this forum:

You cannot reply to topics in this forum