2019.05.DD - Classic Rock - Interview with Duff

3 posters

Page 1 of 1

2019.05.DD - Classic Rock - Interview with Duff

2019.05.DD - Classic Rock - Interview with Duff

DUFF MCKAGAN

The man best known as the bassist with the Most Dangerous Band In The World talks about Guns N' Roses, a life in music, near-death, break-ups, make-ups, the journey from alcoholism to sobriety and his soon-to-be-released solo record. Oh, and a new GN'R album.

Interview: Paul Elliott

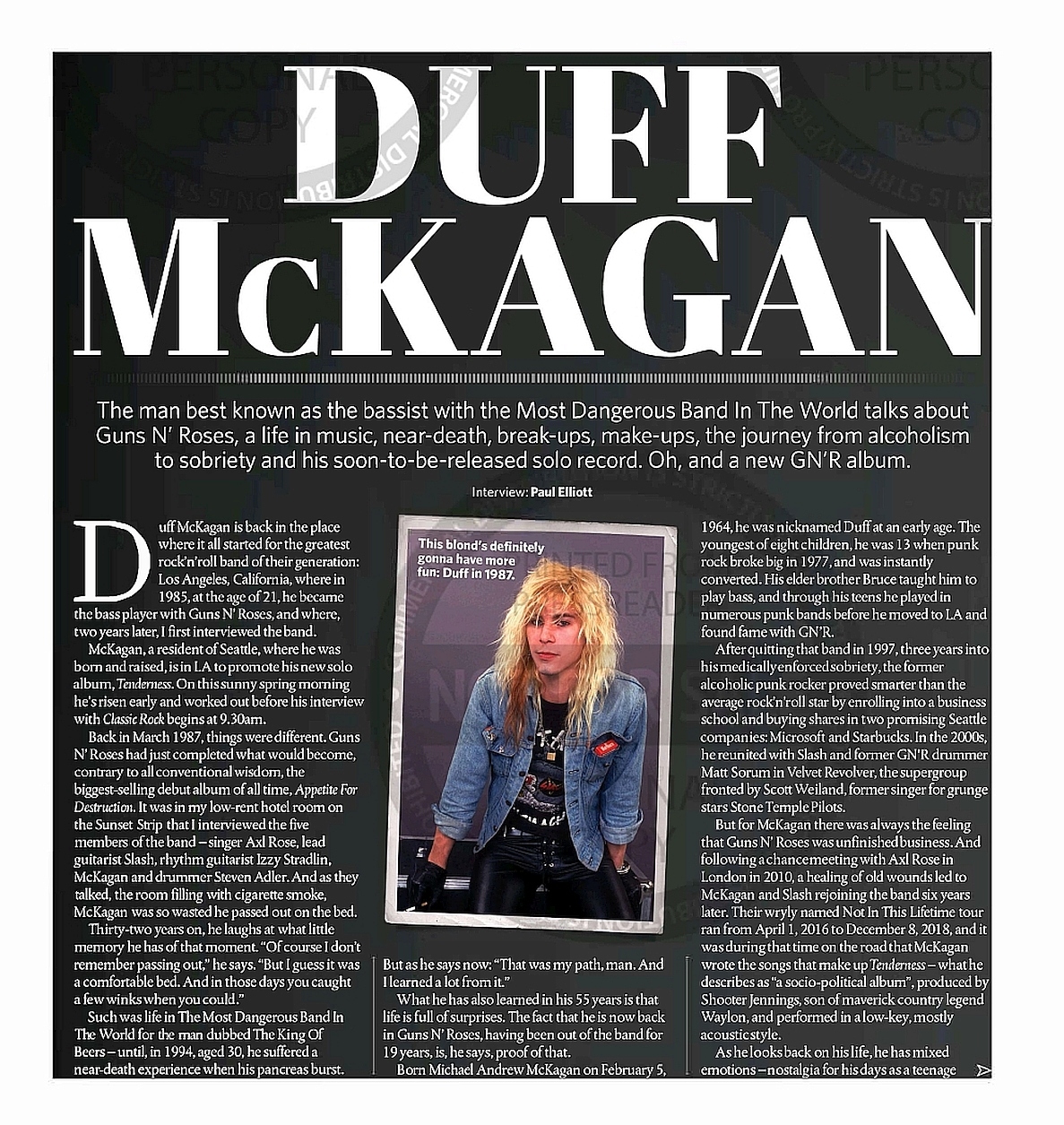

Duff McKagan is back in the place where it all started for the greatest rock ’n’ roll band of their generation: Los Angeles, California, where in 1985, at the age of 21, he became the bass player with Guns N’ Roses, and where, two years later, I first interviewed the band.

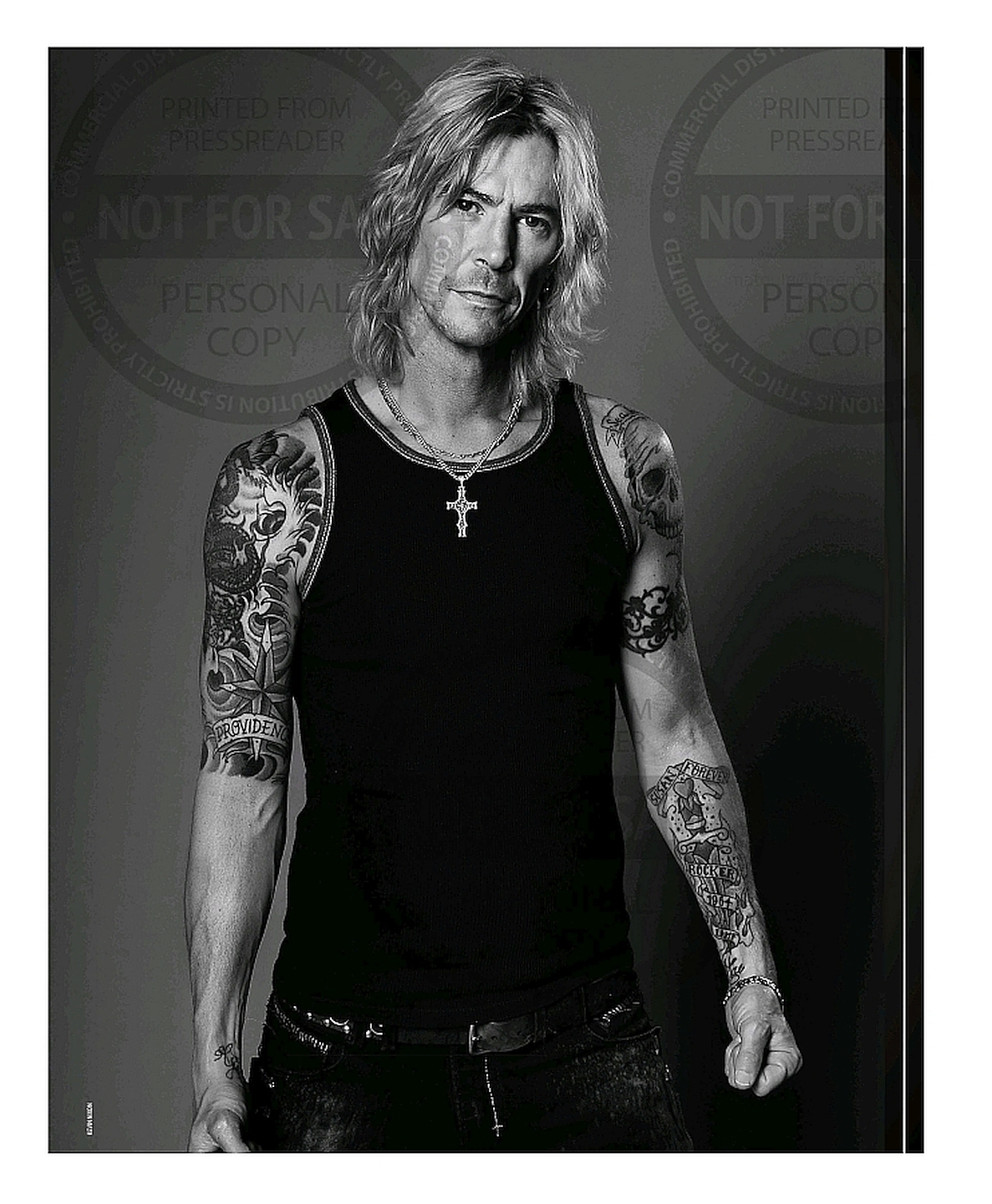

McKagan, a resident of Seattle, where he was born and raised, is in LA to promote his new solo album, Tenderness. On this sunny spring morning he’s risen early and worked out before his interview with Classic Rock begins at 9.30am.

Back in March 1987, things were different. Guns N’ Roses had just completed what would become, contrary to all conventional wisdom, the biggest-selling debut album of all time, Appetite For Destruction. It was in my low-rent hotel room on the Sunset Strip that I interviewed the five members of the band - singer Axl Rose, lead guitarist Slash, rhythm guitarist Izzy Stradlin, McKagan and drummer Steven Adler. And as they talked, the room filling with cigarette smoke, McKagan was so wasted he passed out on the bed.

Thirty-two years on, he laughs at what little memory he has of that moment. “Of course I don’t remember passing out,” he says. “But I guess it was a comfortable bed. And in those days you caught a few winks when you could.”

Such was life in The Most Dangerous Band In The World for the man dubbed The King Of Beers - until, in 1994, aged 30, he suffered a near-death experience when his pancreas burst.

But as he says now: “That was my path, man. And I learned a lot from it.”

What he has also learned in his 55 years is that life is full of surprises. The fact that he is now back in Guns N’ Roses, having been out of the band for 19 years, is, he says, proof of that.

Born Michael Andrew McKagan on February 5, 1964, he was nicknamed Duff at an early age. The youngest of eight children, he was 13 when punk rock broke big in 1977, and was instantly converted. His elder brother Bruce taught him to play bass, and through his teens he played in numerous punk bands before he moved to LA and found fame with GN’R.

After quitting that band in 1997, three years into his medically enforced sobriety, the former alcoholic punk rocker proved smarter than the average rock ’n’ roll star by enrolling into a business school and buying shares in two promising Seattle companies: Microsoft and Starbucks. In the 2000s, he reunited with Slash and former GN’R drummer Matt Sorum in Velvet Revolver, the supergroup fronted by Scott Weiland, former singer for grunge stars Stone Temple Pilots.

But for McKagan there was always the feeling that Guns N’ Roses was unfinished business. And following a chance meeting with Axl Rose in London in 2010, a healing of old wounds led to McKagan and Slash rejoining the band six years later. Their wryly named Not In This Lifetime tour ran from April 1, 2016 to December 8, 2018, and it was during that time on the road that McKagan wrote the songs that make up Tenderness - what he describes as “a socio-political album", produced by Shooter Jennings, son of maverick country legend Waylon, and performed in a low-key, mostly acoustic style.

As he looks back on his life, he has mixed emotions - nostalgia for his days as a teenage punk rocker, pride in how Guns N’ Roses shook the world, gratitude for his survival, and sadness for those friends who never made it this far, among them West Arkeen, co-writer of the GN’R classic It’s So Easy, Scott Weiland and Chris Cornell.

McKagan is fatalistic. “Everything in my life happened according to how it was supposed to happen,” he says. And while he begins this conversation by talking about the inspiration for his solo record, that’s not the only new album on his mind.

You named your album Tenderness. Is that what the world needs a little of right now?

I think this is the most extraordinary period in our lifetime. When America comes together, like on 9/11, nobody asks who you voted for. But now, I turn on cable news and see people yelling at each other. The America I know is different. So what are you gonna do? You know, what did you do when the world was freaking out?

So I chose to write somewhat of a healing record. And I think that together we'll get through this.

You believe there are better times ahead for the world?

I wrote this record on the Guns N’ Roses tour. I don’t sit in hotels, I get out. And just from talking to people all over the world, I’m hopeful. Guns N’ Roses, we play to everybody, man. Everybody unites under that umbrella of rock ’n’ roll. So maybe that’s what gives me hope.

Is it, broadly speaking, a concept album?

I guess I just liked the idea of putting a story together on a record. And when I started talking to Shooter [Jennings], he turned me on to a Willie Nelson record from 1974 called Phases And Stages, which is a concept record about a divorce.

There’s also a flavour of country music in the sound of the record.

Yeah, that came from using Shooter’s band, pedal steel and fiddle and violin and really lush backing vocals. But I’ve | done different kinds of music before with the Walking Papers, which was more like subtle blues. Another big influence on this record was the song 49 Hairflips by Jonathan Wilson. The first time I heard that song, I was driving and had to pull over, it was so good. I tell everyone: “Listen to that song. It’ll blow your fucking mind.’

You say Tenderness is a socio-political album, but it also has songs that are deeply personal; Feel was written after the suicide of your friend Chris Cornell.

The song is a memorial for Chris and Scott [Weiland] and also Prince and Chester [Bennington]. I was trying to highlight a bigger subject, which is suicide and depression and drug addiction, in sort of a poetic way. Chris and I were close in the last ten years of his life. My youngest daughter and his eldest daughter were born two weeks apart, so we were together a lot when the girls were small. And I'd known him since we were kids back in Seattle. The same age, same place, grew up in that punk rock scene...

And it was in that scene that you cut your teeth.

I played in twenty-nine punk rock bands in Seattle - I counted them. I was a drummer, bassist, guitar player, whatever.

You joined the first of those bands, The Pennies, when you were just fourteen. How old were you when you got into drinking and doing drugs?

I started really young. I was smoking weed in fourth grade [aged nine or ten]. And in Seattle mushrooms grow everywhere, so you could just pick them on the way home from school. By the time I was fourteen I was experimenting in everything - cocaine, Quaaludes, a lot of psychedelics. I was doing too many drugs. I was having panic attacks, which I thought was from doing LSD. So I stopped around sixteen. I went straight-edge for maybe a year and a half.

Which punk records had the biggest influence on you?

I loved Black Flag’s Damaged, and The Germs’ (GI) was a big deal for me. That record changed the course of American punk rock. But I listened to the Stones and Led Zeppelin too, and I was always into R&B stuff - Marvin Gaye and Prince.

At the end of the 80s you named Prince's 1999 as the best album of that decade, and said it had a profound effect on you.

It was a changing point in my life. When that record came out, in ’82, I was eighteen. All these punk kids from the suburbs had shaved their heads and started lighting at the shows, doing Nazi salutes and all that crap - just ruining punk rock in America. And there was a lot of heroin coming into Seattle at that time. The band I was in, 10 Minute Warning, got signed by [Dead Kennedys singer] Jello Biafra’s label Alternative Tentacles. It seemed like we were on our way to being the next big thing, and the heroin came in and just ravaged that band. At that point I was drinking again, maybe more than average. But my friends started using heroin. My girlfriend was strung out, my roommate was strung out. It seemed like it was closing in on me. And that was when 1999 became the soundtrack to my life. I loved what Prince did on [1981 album] Controversy. It was really cool, kind of punk rock and kind of Sly & The Family Stone. And with 1999 I was really diving into those songs. It was all the things that music is supposed to be - your solace, your best friend, an escape... And through that record I made the decision to move to LA.

How come?

I’d seen what Prince had done by himself, and I figured if he can do all of that, the least I can do is go to LA. It was a scary thing to do when you’re nineteen, going to a place where you know nobody. But I figured I could sell my drum kit, so I had three hundred and fifty bucks. And yeah, it was 1999 that gave me the courage to do it.

Before leaving Seattle, you wrote a phrase, the beginning of a song lyric, about yearning for a better life and what you hoped to find in LA: ‘Take me down to the paradise city, where the grass is green and the girls are pretty.'

It was just something I wrote like a poem. I had an art book for drawing and painting and writing lyrics – my punk rock idealistic art thing. I don’t know what happened to it.

And those words ended up as the chorus to one of the most famous rock songs of all time.

It’s strange when it becomes that, right? If it was just you and I back then, looking at what was written on that piece of paper, you might think it’s a little goofy. But as the chorus of Paradise City it struck a chord with a lot of people.

When you got to LA in 1984, how did you feel?

I felt poor! I had a bass and an amp and a guitar, and I had to pawn the guitar a couple of times just to make rent. But two of the first people I met were Slash and Steven [Adler], and those guys were really cool, introducing me to stuff. I suddenly had a new little social circle. And in the first month I was there, Slash took me to an LA. Guns show, so I saw Axl singing for L.A. Guns, and for me he was like Henry Rollins. It was real, it was dangerous, he broke a glass on stage, and I was going: “Yes!” His voice was incredible. That was when I realised I’m not in Seattle any more.

Then what?

I got an apartment, and Izzy moved in across the street. I saw him at a phone booth, this Johnny Thunders-looking dude, and I thought: “Okay, we got something in common.” So we get talking, and I can tell he’s high, but at this moment I’m used to it, like, okay. He said he’s starting this band with his friend Axl. I said: “I just saw that guy fucking play. He’s your friend?” He said: “Yeah. We grew up together in Indiana.”

The original line-up of Guns N’ Roses, formed in early 1985, had Axl and Izzy alongside guitarist Tracii Guns, bassist Ole Beich and drummer Rob Gardner. You, meanwhile, played for a brief time with Slash and Steven in the band Road Crew.

Yeah. We didn’t play a gig and we didn’t have a singer, but I got to play and get some chops going. That’s when I lost the guitar I’d pawned. Two cops in plain clothes took the guitar away from me because it had been stolen in Seattle before I bought it. So suddenly I'm a bass player. That's gonna be it. I started taking it seriously at that point.

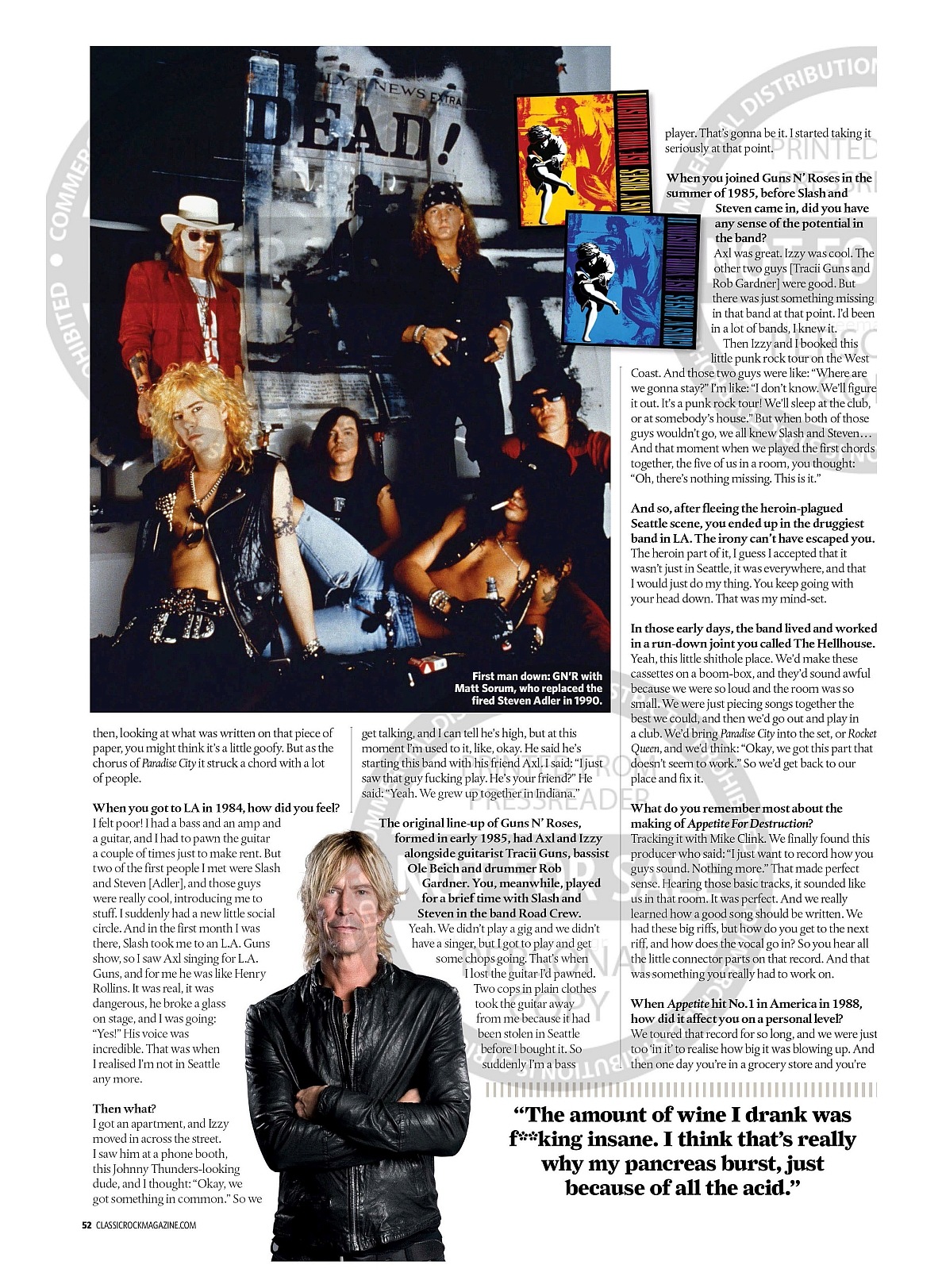

When you joined Guns N' Roses in the summer of 1985 before Slash and Steven came in, did you have any sense of the potential in the band?

Axl was great. Izzy was cool. The other two guys [Tracii Guns and Rob Gardner] were good. But there was just something missing in that band at that point. I’d been in a lot of bands, I knew it.

Then Izzy and I booked this little punk rock tour on the West Coast. And those two guys were like: “Where are we gonna stay?” I’m like: “I don’t know. We’ll figure it out. It’s a punk rock tour! We’ll sleep at the club, or at somebody’s house.” But when both of those guys wouldn’t go, we all knew Slash and Steven... And that moment when we played the first chords together, the five of us in a room, you thought: “Oh, there’s nothing missing. This is it.”

And so, after fleeing the heroin-plagued Seattle scene, you ended up in the druggiest band in LA. The irony can’t have escaped you.

The heroin part of it, I guess I accepted that it wasn’t just in Seattle, it was everywhere, and that I would just do my thing. You keep going with your head down. That was my mind-set.

In those early days, the band lived and worked in a run-down joint you called The Hellhouse.

Yeah, this little shithole place. We’d make these on a boom-box, and they’d sound awful because we were so loud and the room was so small. We were just piecing songs together the best we could, and then we’d go out and play in a club. We’d bring Paradise City into the set, or Rocket Queen, and we’d think: “Okay, we got this part that doesn’t seem to work.” So we’d get back to our place and fix it.

What do you remember most about the making of Appetite For Destruction?

Tracking it with Mike Clink. We finally found this producer who said: “I just want to record how you guys sound. Nothing more.” That made perfect sense. Hearing those basic tracks, it sounded like us in that room. It was perfect. And we really learned how a good song should be written. We had these big riffs, but how do you get to the next riff, and how does the vocal go in? So you hear all the little connector parts on that record. And that was something you really had to work on.

When Appetite hit No. 1 in America in 1988, how did it affect you on a personal level?

We toured that record for so long, and we were just too ‘in i' to realise how big it was blowing up. And then one day you’re in a grocery store and you’re on the cover of Rolling Stone that’s right there as you’re checking out. People are like: “Oh, you’re that guy.” I didn’t really know how to handle that for a while. There’s no kind of training for it.

When I was with the band on a US tour in 1988, you were drinking pints of vodka with just a dash of orange juice for colour. Was that the point when you began to lose control?

I think that came a year later, when we started on the Illusions records [Use Your Illusion I and II]. We were hiding out in this condo in Chicago, and we were fucking raging, just knuckleheads. Well, I’ll speak for myself - I was a knucklehead. When people were getting fucked up, I learned just to take responsibility for my own shit. And I was getting very fucked up. But we still worked hard. We put everything we had into Illusions. And Axl had this amazing thing, November Rain. He’d been working on that song ever since we met.

It was in the early stages of recording those two albums that Steven Adler achieved the seemingly impossible - being kicked out of Guns N’ Roses for doing too many drugs. After all that you’d been through with Steven, you must have felt some guilt.

There was that, and anger, all of these things. We didn’t think we were gonna have to fire him. We thought we’d scare him straight. Especially when we said: “We’re gonna look for somebody else to play on the record...” We thought he’d snap out of it at that point. “No, we really are gonna find another drummer, Steven.” But he just didn’t get better. I wasn’t excluding myself here. Like, deep down, I’m drinking a lot, you know? But I never let it fuck up the sessions. I guess that was when the big-boy pants came on. Like, this is phase two. We got Matt [Sorum], and he did a stellar job on all those fucking songs.

So Steven getting fired didn’t act as a wake-up call for you?

No. I was getting into cocaine, to help me drink longer. I would self-medicate for anything. The band has become huge. And I’m the punk rock guy, I cut my roots. So I’m like, fuck this, man! And I’d gotten divorced [after a two-year marriage to singer Mandy Brixx of LA group the Lame Flames], and that heartbreak thing fucking kills you. So I had the classic self-medicating disorder, and I didn’t have the tools or the time to deal with it. Things were going so fast with the band. But then Izzy got clean.

How did you feel about that?

I was happy for Izzy, but you would stay away from him because you didn’t want to influence him. Then you’re like, shit, how did he do that? Because I would like to do that, you know? It was always in the back of my head: “Next week I’ll get myself cleaned up.” But every time it got pushed back.

When Izzy quit the band in 1991 were you shocked?

I could tell, man. I could see that things were getting to him. On the Illusions tour he was travelling on his own, because he wanted to be away from the influence of the booze and drugs that was going on with us. From our first gig in ’85 to when he left, Iz was to my right side, the closest person physically to me on stage. And that counts for a lot. You can really tell somebody’s mood when you’re playing music with them. It’s a language all of its own. And Izzy’s posture, the way he was playing, the way he’d leave the stage... I could see what was happening.

Izzy was such a key figure in Guns N’ Roses - a major songwriter and, for many, the heart and soul of the band. Did you think you’d be lost without him?

I remember Slash and I talking, desperately, like, how to find a new guy. But when Izzy left it brought Slash and Axl and I closer together. We didn’t have much time. We were on this huge tour. But we got Gilby [Clarke], and as soon as he had it all down - boom! - we were gone.

That tour was one of the longest in rock’n’roll history - 194 shows, running from January 1991 to July 1993. And somehow, in the midst of it you made your first solo record, Believe In Me.

On days off I would go into studios. Was I making demos for Guns? I really didn’t know. I was just recording. And at some point Tom Zutaut, our A&R guy, said: ‘“Let’s put out your own record.” Okay! So I just went ahead and did it, put a band together, and immediately after the Illusions tour I was back on the road for a year. I didn't have the wherewithal to pull back and stop.

How do you view that record now?

There are some cool songs on there, 10 Years and Man In The Meadow, which are somewhat poignant years later in my sobriety.

Can you recall how much you were drinking back then? One estimate put it at twenty bottles of wine a day, which is hard to believe.

I don’t know if it’s possible I drank twenty bottles a day, but I wouldn't put it past me.

Maybe you drank ten bottles and spilled the rest?

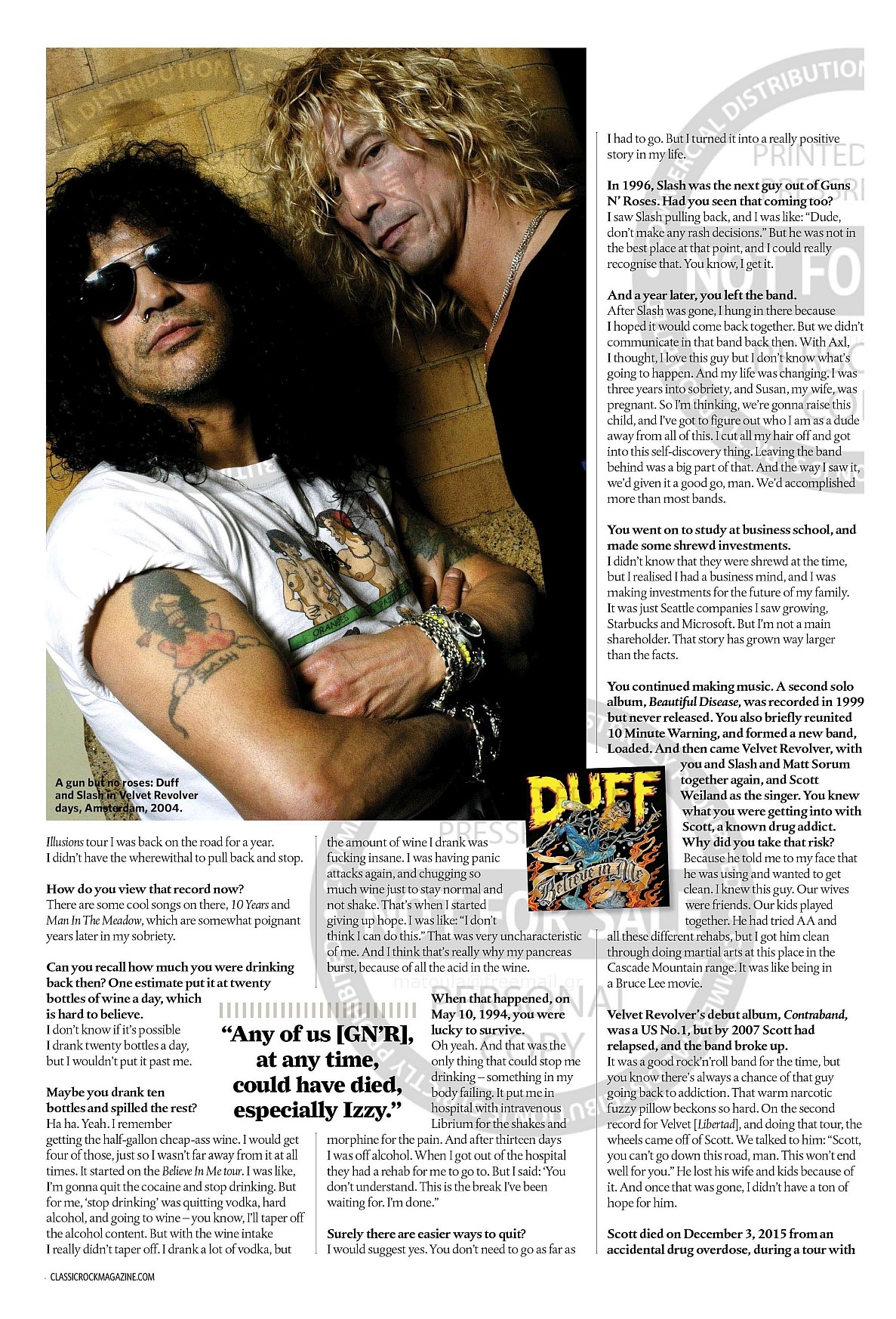

Ha ha. Yeah. I remember getting the half-gallon cheap-ass wine. I would get four of those, just so I wasn’t far away from it at all times. It started on the Believe In Me tour. I was like, I'm gonna quit the cocaine and stop drinking. But for me, ‘stop drinking’ was quitting vodka, hard alcohol, and going to wine - you know, I’ll taper off the alcohol content. But with the wine intake I really didn't taper off. I drank a lot of vodka, but the amount of wine I drank was fucking insane. I was having panic attacks again, and chugging so much wine just to stay normal and not shake. That’s when I started giving up hope. I was like: “I don't think I can do this.” That was very uncharacteristic of me. And I think that’s really why my pancreas burst, because of all the acid in the wine.

When that happened, on May 10, 1994, you were lucky to survive.

Oh yeah. And that was the only thing that could stop me drinking - something in my body failing. It put me in hospital with intravenous Librium for the shakes and morphine for the pain. And after thirteen days I was off alcohol. When I got out of the hospital they had a rehab for me to go to. But I said: ‘You don’t understand. This is the break I’ve been waiting for. I’m done.”

Surely there are easier ways to quit?

I would suggest yes. You don’t need to go as far as I had to go. But I turned it into a really positive story in my life.

In 1996, Slash was the next guy out of Guns N’ Roses. Had you seen that coming too?

I saw Slash pulling back, and I was like: “Dude, don't make any rash decisions.” But he was not in the best place at that point, and I could really recognise that. You know, I get it.

And a year later, you left the band.

After Slash was gone, I hung in there because I hoped it would come back together. But we didn't communicate in that band back then. With Axl, I thought, I love this guy but I don’t know what’s going to happen. And my life was changing. I was three years into sobriety, and Susan, my wife, was pregnant. So I’m thinking, we’re gonna raise this child, and I’ve got to figure out who I am as a dude away from all of this. I cut all my hair off and got into this self-discovery thing. Leaving the band behind was a big part of that. And the way I saw it, we’d given it a good go, man. We’d accomplished more than most bands.

You went on to study at business school, and made some shrewd investments.

I didn't know that they were shrewd at the time, but I realised I had a business mind, and I was making investments for the future of my family. It was just Seattle companies I saw growing, Starbucks and Microsoft. But I’m not a main shareholder. That story has grown way larger than the facts.

You continued making music. A second solo album, Beautiful Disease, was recorded in 1999 but never released. You also briefly reunited 10 Minute Warning, and formed a new band, Loaded. And then came Velvet Revolver, with you and Slash and Matt Sorum together again, and Scott Weiland as the singer. You knew what you were getting into with Scott, a known drug addict. Why did you take that risk?

Because he told me to my face that he was using and wanted to get clean. I knew this guy. Our wives were friends. Our kids played together. He had tried A A and all these different rehabs, but I got him clean through doing martial arts at this place in the Cascade Mountain range. It was like being in a Bruce Lee movie.

Velvet Revolver’s debut album, Contraband, was a US No. l, but by 2007 Scott had relapsed, and the band broke up.

It was a good rock ’n’ roll band for the time, but you know there’s always a chance of that guy going back to addiction. That warm narcotic fuzzy pillow beckons so hard. On the second record for Velvet [Libertad], and doing that tour, the wheels came off of Scott. We talked to him: “Scott, you can’t go down this road, man. This won’t end well for you.” He lost his wife and kids because of it. And once that was gone, I didn't have a ton of hope for him.

Scott died on December 3, 2015 from an accidental drug overdose, during a tour with his band,The Wildabouts. Did you feel that it was always going to end that way for him?

Yes. When I got the news, albeit it was heartbreaking it didn’t surprise me. Like when my buddy West [Arkeen] passed away, it broke my heart but it didn’t surprise me.

What emotions did you feel in 2008 when you first heard Chinese Democracy, the Guns album that Axl made without the old band?

I remember I was working out somewhere, and I heard the song Chinese Democracy. And I was like, okay, he’s got it out. I didn’t have a lot of interest initially. Maybe it was self-preservation or whatever. I didn’t go buy the record and sit there and listen to it all. Maybe I didn’t want to be critical. I just wanted Axl to do his thing, and I always wished everybody the best of luck, deep inside of me. That’s a thing I learned in sobriety.

Ultimately, Chinese Democracy was a flawed masterpiece. Some great songs - There Was A Time, Madagascar - and some not so great.

I came to that same conclusion. It wasn’t until we put the band back together that I got the whole record because I had to learn stuff. And I came to appreciate there are some great songs on there.

It was in October 2010 that you reunited with Axl and played with Guns N’ Roses at the 02 in London. And it happened purely by chance.

I was in London for business meetings, the band was in the same hotel. What are the chances of that? The hotel manager told me: “I thought you were sneaking in for the gigs, so I’ve put you in the room next to Axl.” I thought: “I guess that means it’s time.”

How was it between you and Axl after all that time apart?

It was the first time I’d seen him since I left the band, thirteen years, and it was fucking wonderful, man. We rode in a boat together up the Thames to the 02, and we kind of went back to telling jokes to each other immediately. I got up and played a couple of songs with them. It was cool. I had to leave early because I had a meeting at seven the next morning. Then I wake up the next morning and this whole floor of the hotel is raging, there’s a party going on, and I had to say: “Hey guys, can you fucking chill?” But that night we all went out for sushi, and we had a great time.

So was that the catalyst for the reunion, or is that too simplistic a version?

Yeah, that was the beginning of us getting reconnected. And maybe a year later my band Loaded played a couple of shows with GN’R. That was kind of an olive branch - showing the public, like, there’s

somewhat of a healing going on.

Then in 2014 you ended up playing in Guns N’ Roses on South American tour when the band’s regular bassist, Tommy Stinson, was out with his old band The Replacements.

I was in Australia with the Walking Papers when I got this call: “Could you do these shows? Axl’s in a pickle.” I thought about it a lot. I called Slash and said: “I think I’m gonna do this. He’s in a bind, man, and I'd do if for you.”

So I went and did it, five or six shows. The best part was Axl and I got a chance to talk and hang. And playing those songs, it was like putting on a pair of comfortable boots. It was pretty epic. We realised: this is just two of us, and it has that old kind of nasty swing to it. And, you know, one thing led to another, Axl called Slash, and the three of us started talking.

Did this feel a little surreal to you?

For me, there was always this thing: Guns N’ Roses broke up, and Axl continued on. There was always that elephant in the room, like, what’s gonna happen here? I’m sure you’ve asked me before: is Guns N’ Roses ever going to get back together? I don’t know how many times I was asked that during that big long period. And it was something I was at peace with - within myself. And then all of a sudden, oh shit, out of nowhere we might actually do this!

And once this was agreed between you and Slash and Axl, what did you do first?

I went into my basement, with a boom-box and a little bass rig set up, I started playing all the Appetite songs, and it was awesome! There were all these things that popped out at me: Slash sure is fucking good there; Steven is kicking ass; and Axl, how did he come up with those lyrics? ‘Captain America’s got a broken heart.’ That’s so fucking poignant, and he was so young to have that observation and nail that lyric. I was texting Slash, and he was doing the same thing I was, in his basement. He texted: “These songs are fucking amazing!” And maybe it took being away from it for so long to have that perspective.

Was Izzy ever going to rejoin the band? What’s the truth?

I don’t know what the actual truth is. We definitely wanted him to do it, and I think he entertained the thought, but he never came down and rehearsed. We had amps for him, ready to go. The first month of rehearsal went by... Nothing. Second month of rehearsal came by, and we’re talking to him: “We’re getting close, Iz.” Third month of rehearsal went by... Nothing. I guess he just didn’t want to tour this big and for so long. I love that dude, but I gotta say that Richard Fortus is a hell of a player and we couldn't ask for a better guy.

The first show, on April 1, 2016, was at The Troubadour in LA, where the classic GN’R line-up had made its debut back in 1985. Were you nervous?

Fucking super-nervous! And it was the same with the Coachella shows [on April 16 and 23]. The first one, we played real fast, the whole set. But the second one we calmed down a little bit.

And when you played at Coachella, the news broke that Axl was to sing with AC/DC on their Rock Or Bust tour, after Brian Johnson was forced to pull out or risk total hearing loss. Did you think Axl was crazy to take that on at the same time as the GN’R reunion?

It was actually kind of endearing when he said: “I'm gonna go and try out for AC/DC. And between their tour and ours I can make it all work if I can get the gig.” And we were like: “Dude, you’re gonna get the gig!” Because Bon Scott was his guy and AC/DC is his favourite band. And that range is what’s in his comfort zone. I don't know what his technique is, but he doesn’t damage his voice up in that range. So no, I didn't think it was crazy. He was able to do something that he’s always wanted to do since he was a kid. And of course he was brilliant. Slash and I snuck out to the show in London, to surprise Axl, and it was so cool to watch. He was super-deferential to the band, he’d stand off to one side, and I was like: ‘Alright! Our dude’s killing it!”

On the GN’R tour, after all the years of the band going on stage late - at Axl’s whim - you started every show on time. And in London you went on early!

Yeah, right [laughs]. We’re on! People who’d been outside, drinking - they were running to the stadium. We just got on with it. And that’s what this band is doing now - just getting on with it.

First there was disbelief at you, Axl and Slash getting back together, then again with the shows starting on time. But is the biggest surprise still to come - are you going to make a new Guns N’ Roses album?

Hey, we went on early, didn’t we? Ha ha. You never know with this band. That’s where I’ve landed on this thing. But the stuff s cookin'. Everybody’s on top of their game at this point, musicianship-wise, songwriting-wise et cetera. We have this tour under our belts where we played a ton together. We know our strengths. We’re now looking forward to what’s next, for sure, with GN’R. And after making this solo record, which is kind of mellow, I look forward to getting back to rocking the fuck out. So there’s my answer.

I’ll take that as a yes.

[Very long pause] You’re a good interviewer, Paul. You do the silent thing - let the guy talk. And you were there from the beginning. You’ve been around for this whole ride. You know as well as I do to expect the unexpected, always, with this band. I think that’s the thesis of this story.

And the miracle of this story is that the five guys who made up the Most Dangerous Band In The World are all still alive.

It is miraculous. It’s wonderful. And I don’t know how that happened. Any of us, at any time, could have died. Izzy especially, back in the day. It was like: “'Whooh, this guy’s not gonna last” But now that we’re all around fifty-five, and we’re still here, it’s great.

Would you call that luck?

It’s fortunate, for sure. For me personally, I’m fortunate that I’ve got my wife and kids. That comes first, and always. And I’ve got my band, and that feels good. So my life isn’t chaos. You know, I’ve done that.

You’re in a good place now?

I am. I feel at ease. It’s a good time, it really is.

Tenderness is released on May 31 via UMC. Duff tours Europe later this year.

***

Outtake from Classic Rock's website:

---------------------------------------------------

Duff McKagan: the 12 Records That Changed My Life

By Fraser Lewry (Classic Rock)

Guns N' Roses bassist Duff McKagan picks a dozen discs that guided his path through music

"I left out Jimi Hendrix. I left out Marvin Gaye. I left out so much stuff. Mother fucker!"

Duff McKagan is talking about the records that changed his life, and the usual 10 isn't enough. We've settled on 12, and even then he's not satisfied. He could carry on, but we're out of time.

The Guns N' Roses bassist is nothing if not enthusiastic. Whether it's other peoples' music, or politics, or history, or the mountains of books he consumes, or his upcoming solo album Tenderness, he can talk with the kind of adrenalin-fuelled excitement you don't normally expect from someone who's been in the business so long and (barely) lived to tell the tale.

But then McKagan isn't the sort to retreat to his hotel room and hide away from the world. "I get out and do things and talk to people," he says, "from Kuala Lumpur to Texas to South Africa to Minnesota."

It's the kind of enthusiasm for life that's driven him from his early days in Seattle to his current status anchoring the world's biggest-grossing live act. And it's the kind of enthusiasm that informs his taste in music, which runs the gamut from garage rock to punk, funk and beyond.

Below, Duff McKagan picks the 12 records that changed his life. Tenderness can be ordered now. McKagan is also interviewed at length in the current issue of Classic Rock.

The Sonics - The Witch

"I grew up in Seattle with seven older siblings, so I grew listening to their records, and the first record I learned to play was The Witch by The Sonics, a band from Tacoma, Washington. If you were from Seattle and you loved rock you had to have a Sonics record.

"I thought it was a song about a real witch - I didn't know it was a song about some guy's bad girlfriend. But the record did change things for me. It was just screaming all the way through, and it left its imprint. It was garage rock, although I didn't know that at the time."

Sly And The Family Stone - Greatest Hits

"We listened to Sly & The Family Stone on a reel-to-reel, which we had before we had a turntable. Greatest Hits came out in about 1970, and all of that different instrumentation and all those fucking great backbeats were like magic to me. I was just a kid!"

Led Zeppelin - Led Zeppelin III

"Immigrant Song really kicked my ass. Every part of it. I couldn't play along with it - I was only 10 – but I could sing along with the 'Ah-ah-aaaaah-ah!' part.

"Every Led Zeppelin record had an impact on me, but Led Zeppelin III probably affected my thoughts on music the most."

The Sex Pistols - Never Mind The Bollocks

"I'd been listening to Kiss's Alive! a lot. Great three-chord rock - Strutter and Firehouse and all of that - and then somebody turned me on to The Pistols. Kiss were a great introduction into The Pistols.

"I'm the last of eight kids, and really wanted something of my own. No one in my family knew who the Sex Pistols were, so they became mine. I was too young to know what some of it meant, but it really had an impact. And it led me on to my next record."

Johnny Thunders And The Heartbreakers - L.A.M.F.

"I went to see Walter Lure [Heartbreakers guitarist] play L.A.M.F. a couple of weeks ago. I went to this by myself in downtown LA. There's five dollar parking across the street, and I parked my car. I went in and saw Pirate Love, Born To Lose, Chinese Rocks. That's all I needed. It was great. This record made a huge impact on me.

"Johnny Thunders' playing and Jonsey's [Sex Pistols' Steve Jones] playing: I've played guitar ever since, and that's who I fashion my guitar playing after. I got to play in a band with Steve in the 90s [Neurotic Outsiders], and it was like a dream come true. I started playing guitar and he immediately recognised where I got all my riffs from!"

The Germs - GI

"I had the Nervous Breakdown/Wasted EP by Black Flag, but they didn't have an album out. And then I heard GI by The Germs and I had to decipher it. I was like, "what the fuck is going on here?!?', and then it became the soundtrack to my life."

The Stooges - Fun House

"Of course I discovered The Stooges course after I'd discovered The Pistols and Thunders, so I went backwards. But Fun House wasn't too different from The Sonics, you know? Loose, TV Eye, Down On The Street. How sleazy is that?"

Prince - 1999

"I was turned on to Prince sometime around 1980. I really love For You and Prince and Controversy and Dirty Mind, but there was something about 1999.

"A lot of heroin was going through Seattle, and while I wasn't using, a lot of people were getting strung out: my friends, my roommate, my girlfriend, my band. We had just signed to Jello Biafra's record label and were going to be the next big thing, but a couple of the guys got strung out and it was the end of the band.

"It was 10 Minute Warning, who were a precursor to Soundgarden and Green River and all of that. I was heartbroken, man, seeing all this stuff going on around me, and I knew I had to make a decision. Then 1999 came out in 1982, and I just dove into the record.

"I loved Little Red Corvette. It may be the most perfect three-chord song ever written. But it was the deeper tracks that I loved most. I would get off work and come home and just play the record and it was my escape.

"Everybody has that record that 'saved their life', and 1999 gave me the courage to stand on my own two feet. It gave me the courage to leave. I knew my car wouldn't make it to New York, but I knew it could get me to LA. Somehow it encouraged me to do that on my own, and it was scary, but I knew music was going to be my thing."

Mark Lanegan - Whiskey for the Holy Ghost

"It's a record that keeps affecting me. The simplicity of it. The beautiful tapestry that guy creates with his words and his voice. It should be in everybody's record collection, I think."

The Dead Boys - Young Loud and Snotty / Generation X - Generation X

"I'm going to group these next two record together because they had a huge effect on me. The Dead Boys' Sonic Reducer was one of the first songs I learned to play"

"And Generation X were impossibly good. They had the best drummer. The best bass player. The best guitar player. The best singer. And the best songs. Kiss Me Deadly was like a ballad, and when I heard them sing about a 'tube to Piccadilly' I was like, 'What is a tube?' 'What are these stations?'

"Back then punk rockers in my town would get beaten up for looking different. So yeah, I really identified with that song."

Refused - The Shape Of Punk To Come

"This record kind of saved rock'n'roll when it came out in 1998. I have a lot of respect for that band, and I went and saw them when they regrouped. Another show I went to by myself. You don't take somebody who doesn't know the band. In Seattle, they played the Showbox, and I drove down and just sat there and watched their whole set without distraction.

"That record was really fucking amazing in so many different aspects. Hardcore to jazz to electronic disco, but it's a really great body of work. It's an album."

https://www.loudersound.com/features/duff-mckagan-the-12-records-that-changed-my-life

Last edited by Blackstar on Wed Jan 03, 2024 12:25 am; edited 7 times in total

Blackstar- ADMIN

- Posts : 13906

Plectra : 91369

Reputation : 101

Join date : 2018-03-17

Re: 2019.05.DD - Classic Rock - Interview with Duff

Re: 2019.05.DD - Classic Rock - Interview with Duff

Again, Duff is strongly implying they will make a new record

Soulmonster- Band Lawyer

-

Posts : 15971

Plectra : 77388

Reputation : 830

Join date : 2010-07-06

Re: 2019.05.DD - Classic Rock - Interview with Duff

Re: 2019.05.DD - Classic Rock - Interview with Duff

I added the full version of the interview.

Blackstar- ADMIN

- Posts : 13906

Plectra : 91369

Reputation : 101

Join date : 2018-03-17

Re: 2019.05.DD - Classic Rock - Interview with Duff

Re: 2019.05.DD - Classic Rock - Interview with Duff

thank you so much! i went to the store to read the interview but the new issue was already on the shelves and I missed out

whatashame-

- Posts : 35

Plectra : 2802

Reputation : 2

Join date : 2017-09-16

Similar topics

Similar topics» 2019.12.10 - Classic Rock - Interview with Duff

» 2004.07.DD - Classic Rock - Interview with Duff

» 2019.06.10 - Planet Rock/The List - Duff McKagan recalls 'nerve-wracking' classic Guns N' Roses reunion show

» 2019.05.01 - 101 WRIF Talkin' Rock with Meltdown - Interview with Duff

» 2009.04.DD - Classic Rock Revisited - Sick Things: An Exclusive Interview with Duff McKagan

» 2004.07.DD - Classic Rock - Interview with Duff

» 2019.06.10 - Planet Rock/The List - Duff McKagan recalls 'nerve-wracking' classic Guns N' Roses reunion show

» 2019.05.01 - 101 WRIF Talkin' Rock with Meltdown - Interview with Duff

» 2009.04.DD - Classic Rock Revisited - Sick Things: An Exclusive Interview with Duff McKagan

Page 1 of 1

Permissions in this forum:

You cannot reply to topics in this forum